By Gianna Campillo ’25

Managing Editor

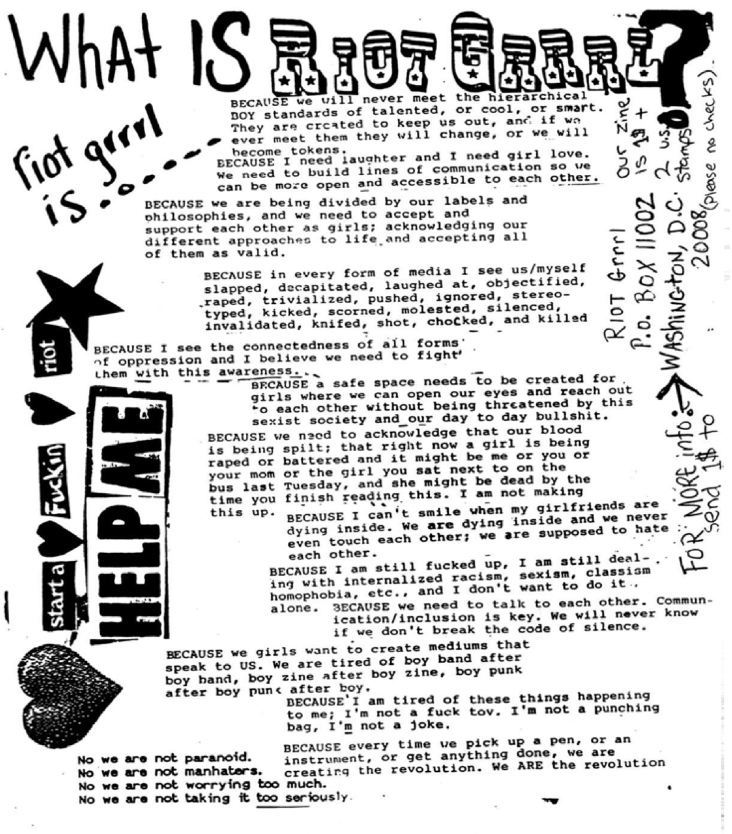

Chasing the nostalgia of the ‘90s, teenage girls nowadays have replaced zines with digital mood boards. Their pinterest boards overflow with collages portraying female punk rock icons clipped to pink pages with colorful stickers and feminist adages. The inspiration? The feminist punk subcultural movement “Riot Grrrl.”. Looking beyond the aestheticism of ‘90s feminism poses an important question—was Riot Grrrl the intersectional movement it claimed to be, or rather, a repressive “outlet of expression” created by and for white women?

Lisa Darms, ed., “The Riot Grrrl Collection,” in The Riot Grrrl Collection (New York, NY: Feminist, 2013).

Riot Grrrl began as an underground movement in the punk scene in the early 1990s, becoming popularized through homemade magazines, or “zines,” in order to discuss subjects such as feminism, anarchism, sexuality, and racism. It is questioned whether the movement successfully created insightful and profound discussions about such topics? Some criticize the movement as a negligence of intersectionality, while others perceive it as the beginning of third wave feminism, launching discussions about tackling marginalized women’s issues.

“The Riot Grrrl Revolution.” Equality Archive, October 12, 2017. https://equalityarchive.com/issues/riot-grrrl-revolution/.

As white artists were propelled to the forefront of the female punk scene, Riot Grrrl’s target audience quickly became dominated by white suburban teenagers. Bands with all white members, such as Bikini Kill and Le Tigre, became faces of the movement. On the other hand, women of color in the punk scene felt unwelcomed and excluded from participating in the movement. Michelle Cruz Gonzales, a Xicana in the band Spitboy, explicitly declared that her group was not a Riot Grrrl Band, as they did not feel supported or seen by the movement.^1 In the late ‘90s, musician Tamar-kali Brown decided to form an alternative to the white dominated Riot Grrrl movement called “Sista Grrrl Riots,” in which she rallied black female artists to headline concerts. ^2 The dominance of predominantly white musicians prevented minority artists and listeners from inserting themselves in the scene, resulting in many WOC completely rejecting the movement to form their own.

Photo by Honeychild Coleman, 1997.

The movement’s largely homogenous audience was continuously reaffirmed through the use of zines. These were handmade magazine collages positioned as creative outlets for adolescent girls to voice their opinions and connect with one another. The production of zines was a costly and time-consuming process, hindering many lower income WOC from participating in the artistic formation of female networks. A 1992 Newsweek article confirmed that the typical Riot Grrrl was “young, white, urban and middle class.”^3 The Riot Grrrls of color who did create their own zines struggled to amplify their voices. Ramdasha Bikceem created her zine GUNK at fifteen years old, initially writing about her band but eventually shifting to venting about her experiences with the intersection of racism and sexism. She engaged in Riot Grrrl culture as a critic and participant, even attending the movement’s first convention in Washington DC in 1991. Aside from the convention being filled with mainly white attendants, Bikceem recalls visiting one of its panels about racism. She notes that the panel was largely ineffective, as it was created and run by white girls for a white audience, causing her to feel like the movement was some kind of “secret society” that she held mixed feelings towards.^4

Darms, Lisa. “Grrrl, Collected.” The Paris Review, July 30, 2013. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/07/30/grrrl-collected/.

The glaringly minimal representation of WOC was never truly enough to effectuate change, and discussions of the intersection between racism and sexism were rarely brought into the limelight. White Riot Grrrls sometimes brought up race in their zines, questioning how they could be better allies to marginalized communities. These women who attempted to create awareness about racism in their zines were often unable to express valuable insight other than being “defensive or apologetic about their whiteness.”^5 They often criticized the bourgeois mentality of white men, failing to recognize the same positions of privilege they claimed as white women. Many Riot Grrrl zines suggested methods of empowerment for all women to mitigate sexism—but women of color could not alleviate misogyny in the same way white women could. White Riot Grrrls often advocated for women to reappropriate sexist diction (i.e. words like “slut”) in order to reclaim their sexualities. However, women of color were ridiculed and fetishized in a way that white women were not, therefore hindering their ability to reclaim this aspect of their lives. Many white Riot Grrrls spoke over the voices of marginalized women, speaking for feminist issues without realizing that they were failing to represent all women.

Lisa Darms, ed., “The Riot Grrrl Collection,” in The Riot Grrrl Collection (New York, NY: Feminist, 2013).

Generally, the Riot Grrrl movement advocated for “women’s issues,” failing to consider the interconnectedness of race, gender, and class. Zines as a medium of projecting the voices of girls to relate in their shared experiences of sexual assault and discrimination was a powerful intersection of creation and allyship. However, these connections developed through Riot Grrrl publications largely ostracized women of color, excluding them from this valuable network of support. White, middle-class Riot Grrrls typically painted themselves as the sole victims to the sexist culture they lived in, without admitting the advantages they held over their female peers of color. Many participants of Riot Grrrl could not recognize that women of color were forced to prioritize protecting themselves from violent forms of racialization before dealing with many of the issues of sexism white women wrote about. Initially, the idea of Riot Grrrl was appealing to many WOC, but they soon felt compelled to part ways with the movement. One of the movement’s most notable pioneers and members of Le Tigre, Johanna Fateman agreed that Riot Grrrl was not a true intersectional movement. She questioned: how could girls in this white dominated scene “forge a truly inclusive, revolutionary agenda?”^6

Personally, I think that we should bring back zines as a means of forging female collectivity, spreading girl love, and fostering new forms of empowerment. Just so long as this time, as opposed to the ‘90s, they could actually be a tool of connecting women across borders and racial groups.

End Notes

1 Gonzales, Michelle Cruz, Mimi Thi Nguyen, and Sorrondeguy Martín. The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016.

2 Bess, Gabby. “Alternatives to Alternatives: the Black Grrrls Riot Ignored.” VICE. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en/article/9k99a7/alternatives-to-alternatives-the-black-grrrls-riot-ignored.

3 Staff, Newsweek. “REVOLUTION, GIRL STYLE.” Newsweek. Newsweek , March 13, 2010. https://www.newsweek.com/revolution-girl-style-196998.

4 Schilt, Kristen. “‘The Punk White Privilege Scene’: Riot Grrrl, White Privilege, and Zines.” Essay. In Different Wavelengths: Studies of the Contemporary Women’s Movement, edited by Jo Reger, 44. New York: Routledge, 2005.

5 Ibid.

6 Lisa Darms, ed., “The Riot Grrrl Collection,” in The Riot Grrrl Collection (New York, NY: Feminist, 2013), p. 20.