In his collection of short stories “Dubliners,” James Joyce writes about a young boy infatuated with his friend’s older sister, Mangan. The boy spends his time curating happenstance such that he sees her nearly as often as he thinks of her. Their conversations are few and far between – rushed and inconsistent – until one morning, she asks him if he will attend Araby, a bazaar in Dublin and the title of the story. She herself cannot go and as a boy infatuated, he offers to visit and purchase her a gift. Anticipation of the bazaar takes the same attentive quality of the boy’s anticipation of the girl’s attention, and he spends his day on a new curation: the performance of a boy on a mission, a boy in need of fare for the train, a boy on a schedule. Of course, as is Joyce’s style, the boy’s plans are thwarted by the harshness of reality: the boy’s uncle – the one who is to give him the fare for the train – comes home late; the train – the one in which he can only afford to sit third class – is delayed; the bazaar – the one from which he intends to buy his gift – is closing by the time he reaches it. The story ends with a boy in agony, realizing not only the futility of his mission but also of any hope of a relationship with the object of his infatuation: the exotic sister of his brown friend.

As the title implies, Araby is the story of a Dublin boy and his fixation with a “brown figure.” Throughout the story, the sister – unnamed and defined only through her relationship with her brother – serves as an antidote to the young boy’s boredom: of school, of the Dublin town he lives in, of his day-to-day life with his family. The tragedy of this short story is not the young boy’s failure to buy a gift for the girl, but rather an implied failure of the exotic girl to save the young boy from the perceived monotony of the life he lives. Early in the story, the young narrator states, “I kept her brown figure always in my eye.” Yet, by the end, his gaze – albeit painfully—shifts away.

Fixations on the elusive, exotic, and inevitably evasive “brown figure” of the East plague narratives that attempt to take up the “Arab world” as their subject. Orientalism is as prevalent in the works of white men who write on the Middle East and North Africa region as thoughts of Mangan’s sister are to the young boy in Araby. While this may not be a novel observation, it is one that continually proves itself to be true in surprising ways: most recently, in the release of two singles by the British band, Coldplay.

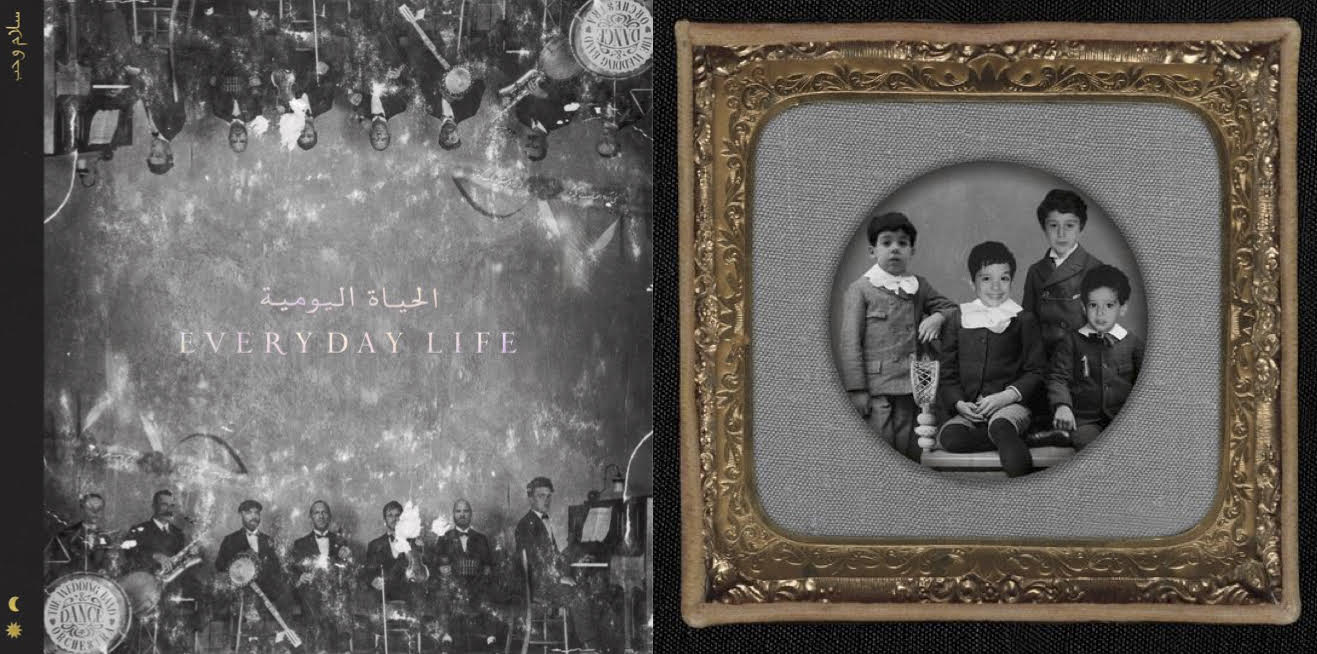

Titled “Orphan” and “Arabesque,” these singles demand to be political. The album cover depicts a faded black-and-white photo of a collection of men seated in a row, holding a variety of instruments. In the center, the words “Everyday Life” are written first in Arabic and then, below, in English. In the top left corner and in a sunny-yellow font, the words “سلام وحب” are written, Arabic for “peace and love” (though translations for the words don’t appear on the album cover). For a band composed of four white men, the design of this album cover is, at the least, unexpected. However, this album cover does not merely evoke a sense of familiarity because it is intentionally aged and looks as though it would be better suited for vinyl: the design of this album cover is oddly reminiscent of an album entitled “The Beirut School,” released in 2019 by the Lebanese indie band, Mashrou’ Leila.

Mashrou’ Leila has established itself as a band committed to activism through song. “The Beirut School” features a collection of their most popular music: songs about injustice in Palestine, songs about queerness and LGBT rights, songs about Arab identity, and songs about desires for political freedom. For years, this band has weaved the political into its music, intentionally and in full consideration of potential repercussions. To date, they have been banned from performing in Egypt and Lebanon for the subject matter of their music and they continue to make headlines for both their successes and for when they are silenced. The members of Mashrou’ Leila write music about the Arab identity as more than a monolithic, heterosexual, conservatively-Muslim thing: they write about Arab people without minimizing them to the base identity of an Arab person; a brown figure; an exotic Other.

What is immediately unsettling about the singles released by Coldplay is that they – unsurprisingly – fail to do the same. They fail to compellingly depict Arab-ness without immediately reducing their subject to a vague “brown figure/ person/girl/ thing.” Consider first their song, “Orphan.” In it, lead singer Chris Martin sings about a girl named Rosaleem, who lived in Damascus with her father until they were both killed, presumably by a missile and as a result of the ongoing civil war in Syria.

“Boom boom ka, buba de ka, Boom boom ka, buba de ka, Boom boom ka, buba de ka,” Martin and the choir harmonize throughout the song.

With no connection to the region, Martin continues to sing about a “baba” (a term of endearment for “father” in Arabic) and the flowers that he once grew on land that could no longer be sown. Confusingly, the song alternates perspectives, with some verses talking about Rosaleem and her father in the third-person and others adopting a first-person perspective. The chorus itself goes:

“Oh, I want to know when I can go

Back and get drunk with my friends

I want to know when I can go

Back and feel home again”*

When listening to the song, the “I” here at times refers to Rosaleem, other times to her father, and still others seems to refer to Martin himself. This vagueness in perspective is perhaps one of the most unsettling components of the song. Rosaleem and her father are only in our gaze for a second before our eyes are forced away and back to the West: to nostalgia for a childhood hazy with intoxication, regardless of how unrelatable such a childhood would be for a young Arab girl living in Muslim-majority Syria. Our gaze is forced back to Martin, and the way that he centers himself in this narrative about Arab trauma.

This blending of identity and perspective is as prevalent in the lyrics of “Arabesque,” maybe even more explicitly. This song begins with Martin singing:

“I could be you, you could be me

Two raindrops in the same sea

You could be me, I could be you

Two angles of the same view

And we share the same blood.”*

Perhaps intended to be comforting, these lyrics are belittling in their blatant reductionism. As if the dichotomy between the East and the West – a division that in part derives from years of militarized imperialism and Western intervention in the name of “security”– could be minimized with a mere proclamation of sameness. A sameness desired with no consideration for which differences must be nullified in order to achieve it: a sameness in which Martins states, “I could be you…” with an implied “but I would not want to be.” Importantly, the root of this sameness has nothing to do with physical appearance, but rather the invisible: we share the same blood. Might we still be the same — might we still be each other — if I am brown;female and you are white;male? Somehow the sameness here feels imbalanced.

This song, too, ends in confusing vagaries as Martin repeats over and over: “Music is the weapon, music is the weapon of the future.” And with these proclamations, Martin – and the band Coldplay by extension – declare themselves to be soldiers in some ill-defined war: these singles the cavalry and the songs of their upcoming album the rest of the troops. In two songs, Coldplay claim to do what Mashrou’ Leila and other Arab artists (El Morraba3, Moe Khansa, and Juliana Yazbeck, to name a few) have been doing for years: engage in political discourse through music about Arab-ness and Arab identity and happenings in the “Arab world.”

While Mashrou’ Leila’s portrayal of these aspects of Arab-ness are far from perfect, and they are not palatable to every Arab-identifying person, they are at the very least partially informed by the lead singer’s experiences in the “Arab world” as an openly gay, Lebanese man. Yet, while Mashrou’ Leila is banned from performing their music in some Arab countries, Coldplay will play not one, but two live shows in Jordan on the day of their album’s release (which is set as November 22, 2019). With advertisements for the album in Jordanian and Emirati newspapers and billboards popping up across Amman, it seems that Coldplay is serious in their attempts to engage the “Arab world” in this new project of theirs.

What remains to be seen, however, is how long this use of Arab-ness as aesthetic will last for the British band that has been together for nearly 23 years. How long until the lights of the bazaar dim and all that is left is a white boy in the dark — his quest to alleviate boredom failed, and the brown figure nothing more than a smattering of red and white dots on the back of closed eyelids.

* Lyrics courtesy of LyricGenius.com.

~Noora Reffat ’19 & ’20