In defense of contemporary romance and in protest to the partition of literature

By Anaiis Rios-Kasoga ’25

An Author’s note

In this piece I talk down a lot on smarties, wanna-be smarties or self-identifying smarties. I am not outright opposed to smarties, I fear if I was I would be a hypocrite not to lay claim that I am myself a smartie, but I will stop using the word smartie and simply say that I am opposed to self-righteous literary snobs who think it’s okay to be a snob simply because sometimes they say smart things.

As an avid reader for all of my childhood and most of my adult life, it is shocking to me now that last spring was my first foray into the romance genre. I attribute the delay to the pressure from the media and my environment to engage with “worthwhile” texts, which romance never seemed to fall into. What was supposed to be a casual departure from my regularly scheduled reading turned into an obsessive spiral into the world of contemporary romantic fiction. It started–as so many things should–with Emily Henry’s Beach Read. The novel follows “a romance writer who no longer believes in love and a literary writer stuck in a rut [as they] engage in a summer-long challenge that may just upend everything they believe about happily ever afters.”

Now if you rolled your eyes at any point during the novel’s synopsis, you need this article and probably also for someone to drop a cartoon anvil on your head and yell –

“Don’t take yourself so seriously!”

In the publishing world fiction is divided up in all kinds of ways though perhaps the most relevant to this point is the distinction between literary and commercial fiction, also called genre fiction. These classifications exist primarily to separate consumers and organize stories by their content. Though the divisions have seeped into the cultural consciousness as all classifications eventually do in such a way that value has been assigned to this content. The most common conclusion being that fiction is by and large better, mentally, intellectually, and culturally if it carries with it the label “literary.” This conclusion is helped along by the fact that genre doesn’t really exist within the label literary. There are themes of course, romantic, horror, psychological, all of the words that could be applicable as genres in genre fiction but the literary novel is not damned by these words in the way that commercial fiction is. Romantic themes that exist in literary fiction are considered “real” while the romantic genre in commercial fiction is considered “fluff.” The former is something that people unapologetically read in public and the latter is hidden on a Kindle or a no-show screen protector.

There is a certain element of misogyny that has to do with the villainization of reading “fluff,” or generally something that doesn’t solely star men and/or isn’t traumatizing and bleak–usually characteristics that make romance “real” in literary fiction–. When thinking about the target demographic for romantic commercial fiction I can almost guarantee that you are picturing a woman probably mid-30s with an unsatisfactory love life. It is a truth that in the current culture and the culture throughout history that if teenage girls or women in book clubs read it’s not real reading because they’re doing it obsessively, or collectively with a glass of red wine. Now how is book club or a teenage girl’s hyperfixation on a leading man different from section men discussing Kierkegaard’s theories of love? It’s the same thing, just trade the girls’ genuine passion for dead-eyed pretension. It’s not different! We see this all over the map, in films and television, in clothing and products. If a woman, particularly a young woman is fond of a given thing then it is decidedly unserious and not worth anyone’s time.

To be a student at a liberal arts institution adds a whole other element to this layered issue. In the Western world, an education in literature is to submit to a cycle of boring long white books that your peers will call “texts,” and pretend are the best pieces of writing they have ever and will ever encounter in their long career of reading things. I love Rory Gilmore as much as the next Ivy League Y2k baby–we don’t talk about season 6–but her relationship with literature conditioned a whole generation of young women to think that if you’re reading BookLovers instead of Dead Souls at 20 you’re some kind of idiot. If Rory Gilmore had experienced the euphoria I felt at reading a slightly broody but at all the right times charming guy who cares and is attentive to his love interest at every point in which it really counts she would love Emily Henry too. Though I would bet money she would hide her copy and deny it belonged to her if questioned.

I bring up Rory Gilmore as my particular pop culture reference primarily because she is one of the points of my own indoctrination into smartie-literary snob-dom; also because her character is much like the well-read educated young women who are just as guilty of perpetuating this partition of literature. If I have to have another conversation with an incredibly intelligent, interesting woman who I otherwise respect about how reading Donna Tartt does not make them objectively better than a reader of Ava Wilder I fear my head might explode splattering my apparent lack of brains all over their well-fitting wool pea coat. However, I must express that I do understand the urge and desire to prove oneself– particularly as a young woman and even more specifically a young woman of color– as a serious reader of serious books who thinks serious thoughts. I’ve been there.

Taught and enforced shame is one of the main reasons why many readers don’t engage with commercial fiction; it is one of the reasons why adult reading peters off so much. The dystopian craze of 2012 was the first time I can recall adults unapologetically reading literature that was widely known to be “unserious.” Though it is important to note the second intellectual male writers and critics read and liked novels like The Hunger Games these books were suddenly verging on literary genius though the novel itself had not morphed into an entirely different title and remained a young adult commercial dystopian novel. These critics could not accept that it was genre fiction because they liked it, and they were right, it is genius.

A boom in popularized adult reading and the social divide between commercial and literary fiction has come to the forefront of a cultural discussion lately largely due to the popularity of BookTok. Again–if you rolled your eyes at the mention of BookTok another cartoon anvil is coming your way. BookTok is a community on TikTok largely occupied by women though there are a few popular male creators where individuals share their recommendations and thoughts on popular books. With the rise of Booktok came a rise of romantic commercial fiction, I believe this to be because in the academic world there is community around literary fiction, “serious books” that “intellectuals read” there was no similar space outside of a local book club to engage with romance the same way.

If people read things they actually liked, adult reading would be a much more popular hobby, we see this playing out on BookTok. Outside of this community people reach the age of 25 and decide that they have to read “serious” books. In the year between 24 and 25 I do not think the average person reaches some kind of enlightenment where Proust suddenly becomes easy reading or reading that is inherently more valuable to the average person than Erin Sterling.

I have read 77 books this year–here’s hoping we hit 100. It’s my goodreads goal– now competitive reading and the culture behind it is another article entirely. I mention this only to say that I would not be reading that much or rather enjoying this much reading if I wasn’t indulging in what made me feel good. Life is too short to spend a bunch of time trying to read books you hate because you think you should like them and you’re embarrassed to read what you actually want to.

The average life expectancy for a person in the United States is 76 years old. Let’s say you read 75 books a year that means that by the time you hit 76 you will have only read 4125 books Now to this I am sure many people –pseudo intellectual douchebags and the like–would say “tsk tsk you brainless plebeian you should make sure that every one of those 4125 books should be important, they should have something to say about society, they should be critically acclaimed, classics, nonfiction, or at the very least literary!”

What are those books worth if you A. didn’t enjoy them and B. they kept you from experiencing perfectly executed enemies to lovers arcs. I would pity you! There’s some kind of catchy quote my boyfriend mentioned as I was writing this. Something about the time you enjoy wasting not being wasted time. All reading is important and if it brings you joy it’s that much better. If you actually derive joy from reading Homer then godspeed but if I tell you that I would rather spend that time reading the newest Emily Henry or that I rated Will They or Won’t They higher on goodreads than The Secret History I maintain that one of those experiences does not make one of us more of a reader than the other.

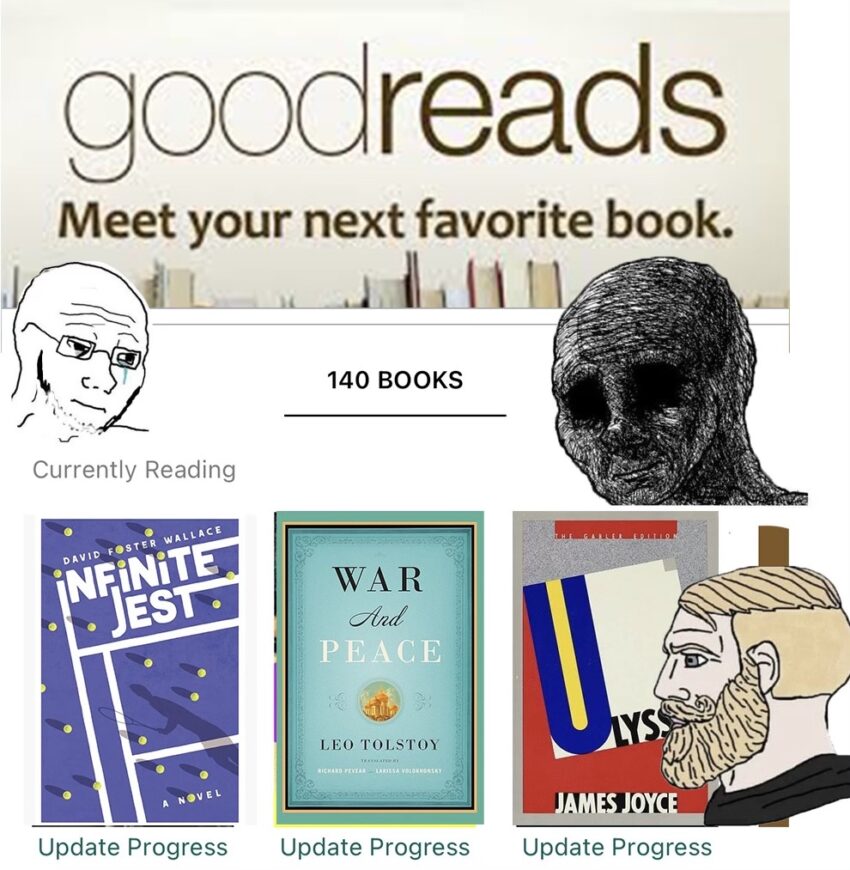

Your average literary snob doesn’t truly know what they like. They know what they’re told to like. Tolstoy bros won’t call a book decent unless it is derived from a foreign–or better yet dead–language. The academics in their woolen sweaters and tiny glasses want a meditation on thinking or a novelization of miscommunication–a romance trope! Normal People is a romance novel Everyone!– that ends tragically. I say blah to that I say let’s see a down on her luck single literary agent fall in love with a hot rival editor. Yes, this is the plot of an Emily Henry novel, no I am not ashamed, yes my copy has cartoon people on it, no I am not ashamed!