A beginner’s guide to know which films are good through Saltburn.

by Collyn Robinson ’25

Writer’s note: If you haven’t watched Saltburn, watch it, then come back to read this piece.

“I love it–no I hate it.” That’s all I could say after watching the movie for the first time.

The reason I watched Saltburn the first time, I’ll admit, was to see Jacob Elordi and I am not ashamed of this fact. But after watching it a second time, for the plot, I believe it should be studied by aspiring young filmmakers on what NOT to do.

In the fantastical, opulent world that Emerald Fennell, the writer and director of Saltburn, creates, she takes the viewer along an aesthetic, indiscernible, and offbeat rollercoaster ride, leaving you with whiplash and unanswered questions. The film ignited discourse around class consciousness, desire, obsession, and power, but Fennell did no work to depict those themes in a valuable or meaningful way, just a pretty one.

As the credits began to roll, I was left with three questions: 1) Who was this film for? 2) Has the writer/director dabbled in the experiences she is trying to replicate through film, or is she just a mere spectator who has observed the phenomenon of the haves and have-nots? 3) Is aestheticism alone sufficient to constitute a good movie?

To answer the first question, the film was made for cinephiles and the hyperparanoid wealthy. In my opinion, Fennell produced a solid piece of cinema that can be studied with its flaws and all. Through Saltburn we learn she has extensive knowledge of the history of film; you can spot the ways in which she pays homage to the old, traditional cinema through her framing, mise en scène, and unique shots. You can also spot her inability to create a robust and reliable story with a satisfying button-ending structure through her wasteful use of characters, resulting in a lack of development and plot holes, ultimately leaving audiences bewildered.

She also takes the idea of “write what you know” and runs with it. The layman/run-of-the-mill viewer doesn’t know or understand this, which is why some audiences left theaters dissatisfied and/or confused. Fennell unintentionally — with the use of prominent actors such as Jacob Elordi and Rosamund Pike — garnered an audience of ignorant viewers who were incapable of finding meaning through images and/or not able to relate to the coterie experiences of attending an institution like Oxford or the Saltburn clan.

To answer the second question, I don’t know whether Fennell wrote Saltburn from inside or outside the house, or castle rather, but she drew her inspiration for Saltburn from somewhere, and it greatly impacted what ended up in theaters. The grey area that is the ambiguous meaning of Saltburn, I suspect, is a result of Fennell not knowing what the real objective of the movie was. She had an idea for a movie, wrote a script that lays the entire plot out in double entendres and innuendos but lacks cohesiveness and got famous people to agree to act in it so Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Amazon, and Warners Bros. could produce it.

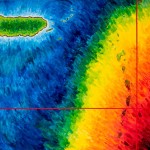

Answering the final question, I believe young filmmakers should NOT follow in Emerald Fennell’s footsteps but should use it as a case study nonetheless. A rationale for this can simply be put into a Venn diagram.

A film is more than just pretty shots and good music, it comes from a complete understanding of the message you want to convey — which if you haven’t realized already is lacking in Saltburn.

As you watch Saltburn again and again for years to come, ask yourself, what kind of filmmakers are the ones you want to keep watching?