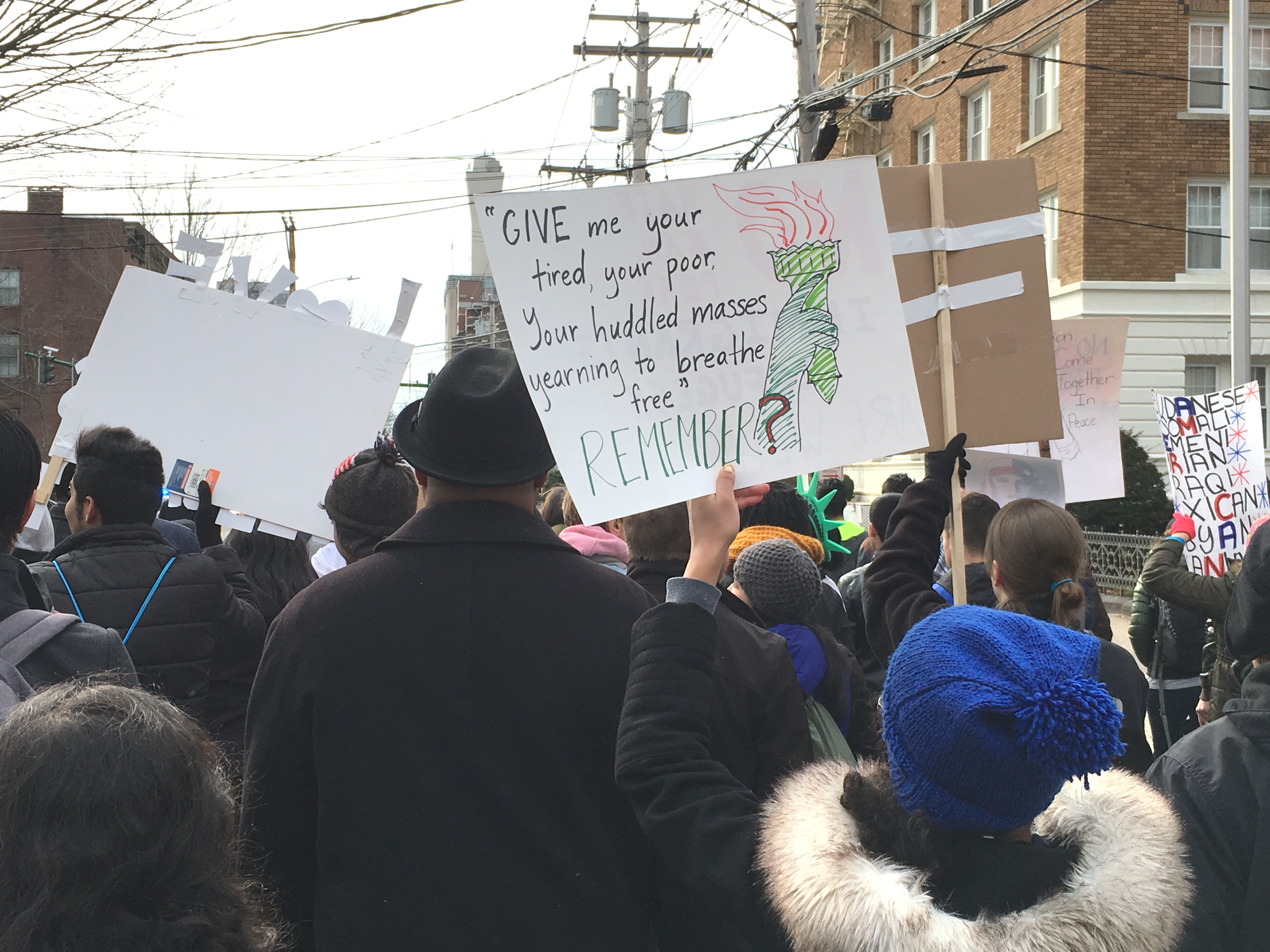

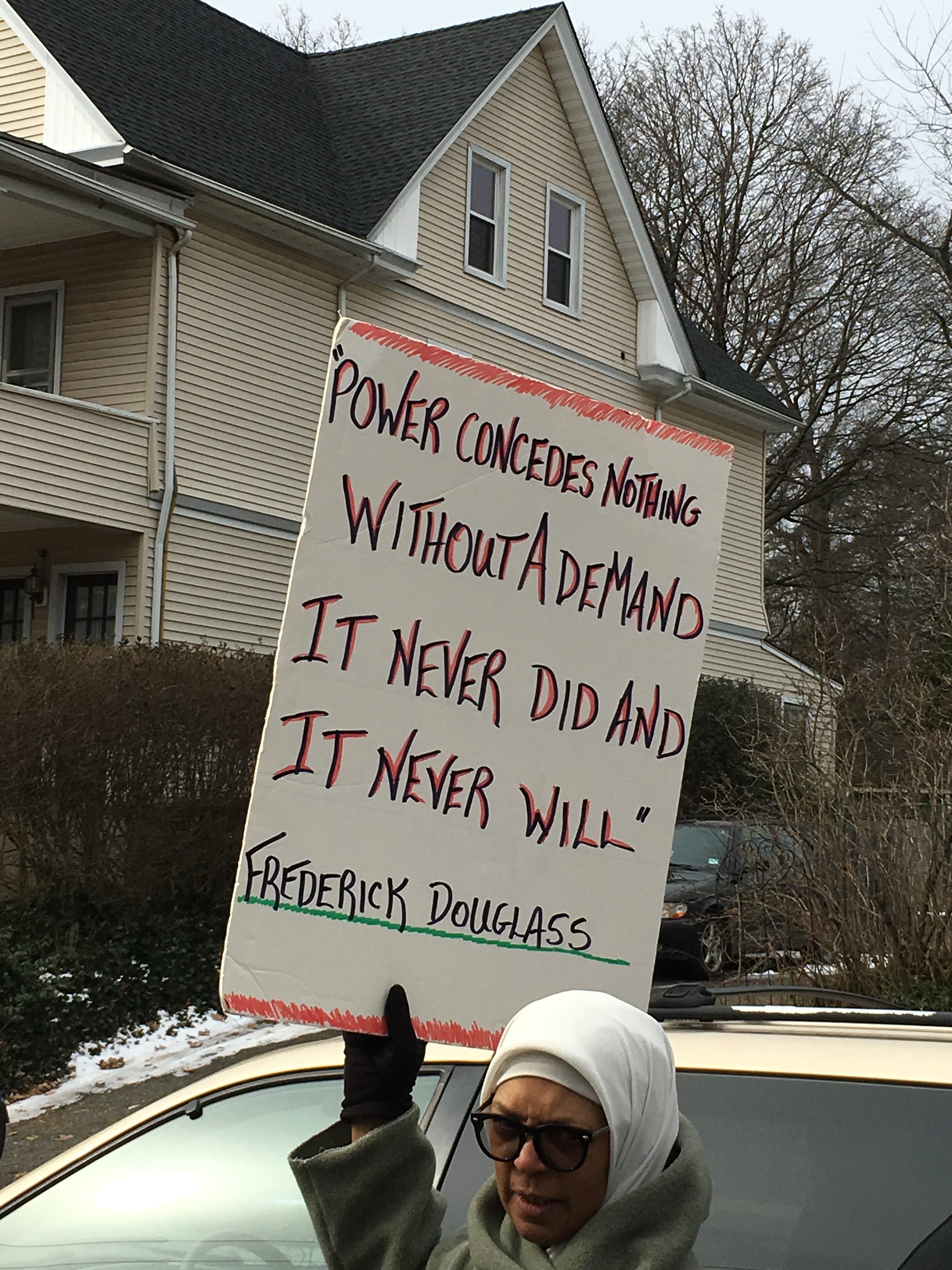

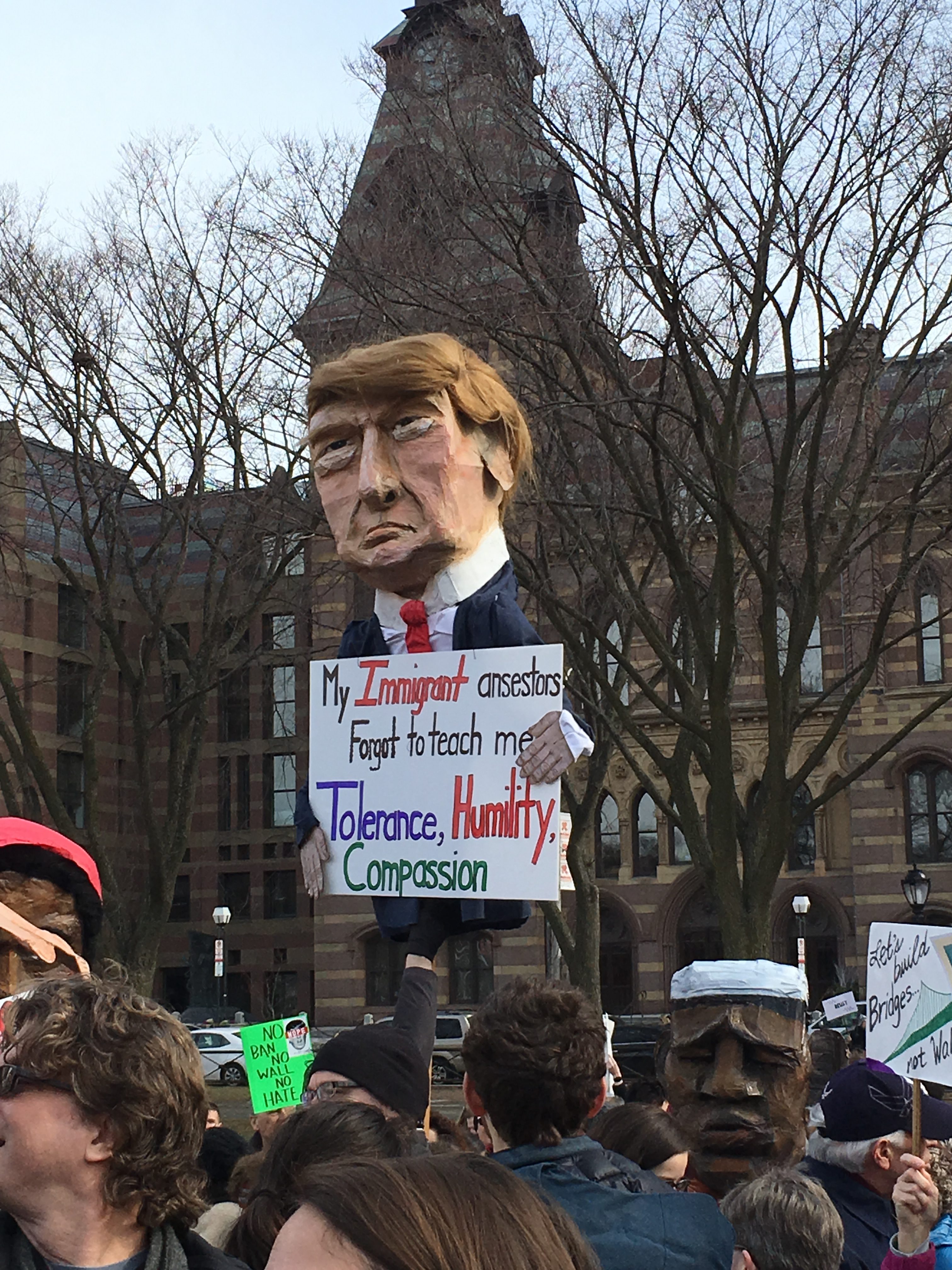

In a bold act of rebellion against President Trump’s recent travel ban, thousands of New Haven citizens and students took to the streets Sunday, February 5, to participate in an early morning 5k run, followed by a march to the New Haven Green. The march, organized by a local chapter Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services of (IRIS), brought in several high profile speakers including Senator Richard Blumenthal, Senator Gary Winfield, Congresswoman Rosa DeLaurio, and New Haven Mayor Toni Harp. Local refugees and immigrants also shared their stories and urged the public not to turn their backs on similar families who have lost everything in their journey to America.

One speaker passionately asked the crowd in Arabic, “Who of you is born knowing who they would become? Who chose their father? Who would choose to become a refugee? Who would choose to lose everything, to have to seek refuge in another country? I am a refugee.”

An Iraqi refugee and photographer spoke encouragingly of the power of demonstrations such as Sunday’s, and cited his own history of journalistic activism to convince the crowd that their actions would not go unnoticed. “In Iraq, we are allowed to have a gun, but we are not allowed to have a camera,” he said. “Because with a gun, you can kill one or two, but with a camera, you can show the world what is going on there.”

Following the remarks of the refugee and immigrant families, the invited government representatives delivered welcoming and empowering commentary in support of refugees and immigrants.

Senator Blumenthal spoke first, saying of the United States, “We are not only a beacon of hope and opportunity for the world; we are great because of the talents and energy and intellect and yes, dedication to democracy that immigrants and refugees bring to this great country.” He continued, “Every one of us has an immigrant story. Every one of us has forebearers that came from someplace else.”

Congresswoman DeLaurio echoed Senator Blumenthal’s sentiments. As church bells rang above her, DeLaurio declared, “The ring is true, this is what democracy looks like, this is what we are about in this great Nation…. You are the American Dream… and New Haven has always been welcoming of immigrants and refugees!”

Like Congresswoman De Laurio, Mayor Harp praised New Haven for its welcome support of refugees, but decisively pushed back on Senator Blumenthal’s ‘Nation of Immigrants’ rhetoric. “This was a city that was founded on freedom. And when I think about my history, I will tell you… my ancestors did not come as immigrants willingly.”

Senator Winfield also announced his support for immigrant and refugee programs and praised the crowd for dreaming of a better, more welcoming America. “Dreamers are doers,” he said. “You’re not out here because you think that the fight is over. You’re here because you’re ready to stand up and fight.”

He proceeded to acknowledge Mayor Harp’s remarks, conceding, “My community… didn’t get here in the way that some of the people here got here. We know something about what hate and fear does to a community, and we’re still fighting the effects of hate and fear that have been foisted upon our community for a long time.”

Both Mayor Harp and Senator Winfield’s remarks drew attention to a problem with much of today’s immigrant rhetoric: it implies that all Americans share a common immigrant story in pursuit of the ever elusive “American Dream.” Within this narrative, there is no room for the histories of slave descendants or Indigenous Americans.

While Harp’s comments did push against the erasure of Black Americans in refugee rhetoric, she invoked an ahistorical account of New Haven history by claiming that freedom was a foundational value of New Haven history that was shared by all local peoples.

Harp’s comments resisted the erasure of slave descendants in refugee rhetoric, but were predicated on a particular history that erases New Haven’s Indigenous presence. By claiming that freedom was the foundational value of New Haven history, Harp overlooks the English coercion of the Quinnipiac people into surrendering their ancestral lands and renouncing their traditional freedoms.

Harp’s assertion erases the manner in which colonial forces took advantage of the Quinnipiac people, who had been devastated by a disease outbreak just before contact with English settlers.

In the early 17th century, English military officers identified New Haven, then known as Quinnipiac, as a strategic location for a settlement, and pursued land acquisition to prevent Dutch forces from settling in the area.

Two wealthy Puritan settlers, John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton, landed in Quinnipiac in 1637 and negotiated with the Quinnipiac sachem (leader) Momaguin to establish a peaceful coexistence in the region. The Quinnipiac people had been weakened by the epidemics of 1633 and 1634, and greeted the English with open arms. A peaceful alliance with the English benefitted the weakened Quinnipiacs because the English offered military protection, having just defeated their rivals, the Pequots, in war. The English also offered open trade with the Quinnipiac, promising a boost to the local economy.

After 7 months of coexistence, Davenport, Eaton, and Momaugin negotiated a treaty that transferred land from the Quinnipiac to the English, and allocated a 1,200 acre land tract for the Quinnipiac. This became the first Indian reservation established on the continent. Consequently, today’s New Haven region is home to one of the earliest forms of state-sanctioned segregation against non-Europeans in New England. In other words, the colonial government at the time actively worked to remove Quinnipiac people from daily English life, except for trade purposes.

The English-Quinnipiac treaty that created this reservation benefitted the English far more than it did the Quinnipiac- it allowed the English to harvest timber even within the reservation borders without Quinnipiac consent. It also barred the Quinnipiac from planting corn or establishing wigwams outside the reservation, thus disrupting traditional agricultural practices.

The treaty also was likely viewed differently by the Quinnipiac and the English in terms of land rights, as the two communities conceptualized property and land usage in very different ways. While the English view of property rights was contingent on individual control of specific land, the Quinnipiac held property communally, and thus likely interpreted the treaty as an agreement to live together in peace and to refrain from encroaching too much on English settlements.

Over time, English colonists instituted further regulations and purchased reservation lands from the Quinnipiac, who were forced to sell their ancestral lands and move elsewhere after their traditional economic structures were disrupted by English colonization. The Quinnipiac largely assimilated into neighboring communities, and were never militarily empowered enough to fight for their sovereignty under English rule.

Examining specific Indigenous histories allows contemporary Americans to contextualize their lives in the scheme of settler colonialism, and understand how the establishment of the United States was contingent on the manipulation of Native people. It is possible to welcome refugees and immigrants to New Haven without using rhetoric that erases the histories and contemporary realities of American Indians and slave descendants. While we can redefine the virtues and values of New Haven as aligned under a common dream of an equitable and fair nation for all people, we must always remember that America is not, and has never been, only a nation of immigrants.

For more information on Quinnipiac History, see The Quinnipiac: Cultural Conflict in Southern New England by John Menta.