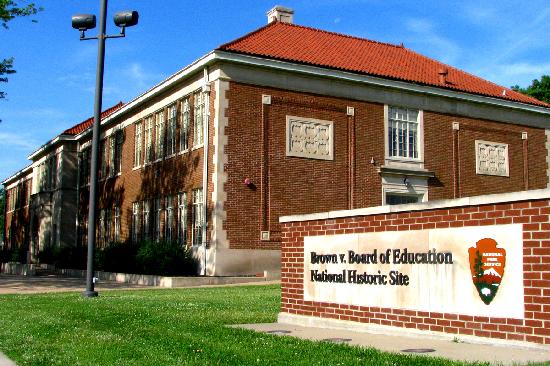

Fernando Rojas, a sophomore in Ezra Stiles College, spent this past summer working at the Brown vs. Board National Historic Site in Topeka, Kansas through a Latino heritage internship program. While at the museum, Rojas completed a project on the history of the Mendez vs. Westminster Orange County School Board (1947) Supreme Court case as a way to study Latinx school segregation in the United States.

In the 1950s, school board policy in Orange County produced Latinx segregation. Official school policy for all students—regardless if they were or weren’t immigrants—was that students who needed to be taught English were to be placed in different schools that would teach them the language. However, there was not official written or oral test to gauge whether or not students needed to be taught English. Student enrollment in so called “Mexican schools” was based entirely on a student’s last name. As a result, the majority of Mexican students were excluded from white, “English speaking,” schools.

The lack of a standardized language test resulted in the occasionally arbitrary placement of Mexican students whose name did not fall under preconceived notions of what a stereotypical “Mexican” name sounded like. When the Mendez family attempted to register their children at the same “Mexican” school as their children’s cousins, they were not able to. Apparently, their names did not fulfill the government’s idea of a Mexican name. Outraged that their children could not attend the same school as their close relatives, the Mendez family decided to sue the Westminster School County.

The NAACP became highly involved in the case, and brought a specialist who researched childhood development to challenge the establishment of “Mexican schools” meant to teach English. The specialist shared her observation that Mexican children did not learn slower than any of their white counterparts and suggested that therefore, there was no need to segregate them.

“It was the first time ‘soft sciences’ like psychology were brought into court,” Rojas said. Ultimately, the Mendez family won the case. The support of the NAACP and the introduction of psychological evidence in the Supreme Court set a precedent for the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case eight years later that desegregated black and white schools in the United States.

Several factors were critical to the success of the Mendez case. While the Mendez family wasn’t the first Mexican family to openly challenge the segregated education system, their case was supported by World War II resources. The land the Mendez family owned was a lease picked up after the original Japanese owners were sent to an internment camp following the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack. With the World Ward II in the background, The Mendez family lawyer used Atlantic ideology to appeal to the justices. Stating that the practice of zoning by ethnicity to only include Mexican families was alarmingly similar to the very Nazi policies that Allied forces were fighting against.

However, Rojas observed that desegregation was not entirely a victory for people of color. “Schools weren’t integrated, they were desegregated,” he said. Mexican students were brought into what used to be white schools but no white students were transferred to formerly Mexican schools. As numbers dropped, teachers at these Mexican schools — mostly of color — lost their jobs.

Rojas is currently turning his summer project into a research paper with the help of Alicia Schmidt Camacho and Ezra Stiles Head of College Stephen Pitti (respectively Professor and Director of Ethnicity, Race, and Migration). After hearing about his summer studying the history of desegregation in the United States, both professors suggested he take their joint graduate seminar on Latino Studies.

Rojas looks forward to a future in law and hopes to have a hand in shaping policy that helps those seeking asylum in the United States.