Recently, Beyoncé, a multi-platinum winning artist with billions of fans worldwide released a visual album titled Black is King. While the intentions were to bring pride to Blackness and Black people around the world, the film, which millions of people will now digest, is saturated with stereotypes about the African monolith that continues to bring harm to the people it is meant to uplift. Stereotypes such as animal prints perpetuating a primal image, random face or body paint that have no cultural meaning other than an aesthetic one, the vast savanna, naked well-oiled women, and Beyoncé herself claiming to be the African Goddess Oshun filled the film. The move comes off a bit hypocritical because Beyoncé herself uses these African aesthetics and doesn’t tour in Africa. Artist Noname went viral for criticizing the album’s visuals.

“We love an African aesthetic draped in capitalism. Hope we remember the Black folks on the continent whose daily lives are impacted by US imperialism. If we can uplift the imagery, I hope we can uplift those who will never be able to access it. Black liberation is a global struggle.” She tweeted.

Following the release of her film, Black African and American artists/creators who had taken part in the movie shared videos of themselves overjoyed at the positive visibility. Any critique of Beyoncé’s Black is King was seen as being a “hater” and met with swift backlash on twitter, especially Black twitter. To many it felt personal. Beyoncé’s mother, Tina Knowles-Larson, commented on the backlash in an interview.

“How do you appropriate the culture when you are the culture, you are Black?” she asked. “That’s not what we do.” She finished.

The issue lies in that exact statement. Black is not an all encompassing culture. As a Guinean, I had to learn how to fit into Black American culture. Coming to America, I was bombarded with questions from classmates about my African hut and from teachers about whether African children showered naked in the rain or were naked because of the heat. These questions further stamped my status as an outsider. Even more so, Black American culture is seen as the example in African countries. Black American movies do better in terms of sales than African films. As Noname stated, many Africans will not be able to access the same “wealthy or monarch-like” imagery that Beyoncé has advertised. Everyone in the US and many European countries benefit from the instability in the African continent. Cobalt, which is a precious mineral in the tech industry is found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo– one of the poorest countries in the world. To push this overabundance of wealth is to erase the effects of imperialism in the continent. The US has an influence over African countries and this includes Black American culture. But despite the dominance Black American culture has around the world, US media has helped mold Black American people as uncultured. The misrepresentation in US media is what has many attached to finding culture elsewhere. In the global fight against anti-blackness, tying Blackness to a Pan-African idea which emphasizes diasporic Black culture as a lesser derivative erases the effects colonialism and imperialism have on the diverse peoples and groups in Africa. It also minimizes the diverse diasporic cultures created in the Americas despite the horrific treatment enslaved peoples endured.

So why the backlash? The timing is off. In the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, any critique of internal Black issues is seen as divisive. “We have to write ourselves as people not worthy of being killed” a Yale student states in a conversation about the visual album during a Black Arts Collective meeting.

Beyoncé exploring her blackness outside the US and her connection to her roots with art is valid, however, one has to begin to question the recurring narrative of Black Americans also trying to find their roots and feeling incomplete if they do not “reconnect” with the “tribe” they belonged to. On one hand it is understandable. Coming to the US, was the first time I felt Black–Black with all the stereotypes that came with it. Back in my home country if a student stole, the person suspected would be the recurring class thief or the student who looked visibly poor. This prejudice would be based on class rather than race because of the homogeneity in the country. In the states, no matter how well I dressed or acted if I was the only Black person in the class, I would be suspected, pulled aside and humiliated publicly. It is valid to want to relocate to a country where the Black identity the US has created doesn’t follow you everyday. It is also encouraged to want to be around or raise a family in a place where the threat of police violence and systemic racism doesn’t impact your livelihood. And while there are some cases like the latter statement, the internet is filled with Afrocentrists and people adorning themselves with a random assortment of “African” cloths and jewelry pushing the idea that the Black culture that already exists in the US is not a true culture worthy of being proud of. In most cases, the referred “Blackness”, both the overly positive in Beyoncé’s film, like the notion that Black Americans are descended of gods or royalty, and the overly negative, which emphasizes Black Americans as ghetto and uncultured, is one that the media heavily propagates. Both carelessly pushing a monolith that erases important details that need to be addressed. The truth of the matter is that the damage has already been done and despite race, Black Americans and Black Africans have completely different identities. Yes I am Black and I consider Black American culture my second culture, but outside the US I am Guinean on my moms side and Malian on my dads side. My tribe is Malenke/Mandinka. I am Muslim, and I am more than just Black. The key point here is nuance–something that is actively avoided in US media. The question now is why?

The lack of nuance makes people not question the horrors of American slavery. The US does this in the way it expertly waters down the human rights violations it has and continues to commit. Black American history is not taught in schools effectively. The diluting of history is what makes American slavery so devastating. It is in the wording itself. What happened in the Americas was not only slavery but a genocide. It is mutilation. It is a rape. It is sterilization. It is torture. It is the commodification of human lives. In contrast, I remember being taught about the Holocaust in full detail in elementary school. I remember many of my peers, myself included, shedding tears and wanting to learn more. American slavery is not taught with the same nuance or consideration. Teachers would make worksheets asking about the positives and negatives of US slavery. This is erasure, and it starts as early as elementary school. Wording and nuance is paramount to this discussion. Slavery and indentured servitude existed in the African continent before just never to the extremes American slavery went to. It was mostly in the form of war prisoners of conquered lands for the economic and political advancement of the winning party. Enslaved peoples who ended up in the Americas were not descendants of royalty despite Beyoncé’s video, most were made to be servants to the winning party. When those prisoners were being sold off, they were not told that they would be reduced to less than human. To say that Africans sold out their own people is gaslighting that erases responsibility and nuance. A New York Times article summarized, “enslavement had not been based on race. The trans-Atlantic slave trade, which began as early as the 15th century, introduced a system of slavery that was commercialized, racialized, and inherited. Enslaved people were seen not as people at all but as commodities to be bought, sold, and exploited.” The mindset that enslaved peoples were not autonomous people who could create culture is being pushed in the media to this day.

Another way the Black monolith negatively affects Black Americans is in the subtle way white America, especially in the entertainment industry, uses this trope to distance themselves from acknowledging American slavery in the media. There has been an overwhelming amount of foreign Black actors leading in major films about Black American slavery. In Twelve Years a Slave, Get Out, Us, and Harriet, these Oscar nominated films are all led by non-African American actors. If it is about Blackness, then there is not an argument that one should play over the other. There is racism and anti-black sentiment felt all over the world. These films and stories need to be told for white and non-white audiences alike. However, is this still an argument about nationality, experience and culture between some? Or is white America still afraid to get too close to home? In the white dominated Hollywood industry, appearances of the Black British and the Black American man look the same. The surface level casting can tick off the box of inclusivity and there’s no shadow of guilt: ‘My ancestors definitely didn’t enslave those of Chiwetel Ejiofor he’s not even American.’ The industry and audience are a little more comfortable because Lupita is African and must not be from slaves. Why is this significant? American slavery and the trauma many survivors have endured is passed down from generation to generation. Generational trauma exists. Acknowledging that a wrong has been done and that there are still people today benefiting off of the trauma many Black Americans have endured is the first step for change.

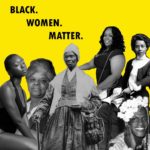

Black Americans despite the trauma inflicted on them for generations pioneered the creation of a culture that is the trendsetter (often appropriated) for movements and culture globally. Enslaved people and survivors, with inspiration from their former and new cultures, created Blues, Jazz, Rock and Roll and much more. Fashion trends and music that are seen as “ghetto” or “rachet” are being mimicked consistently. It is uplifting to see Black people around the world support each other, but acknowledging that we are all different and properly crediting ourselves will humanize us. It is an imperialist strategy to blindly ignore cultural boundaries and carve without care, causing conflict. We need to take a step forward and support purely African art, we need to uplift different Black narratives all around the world. We need to reverse the narrative that different Black cultures are invalid and that white people invented everything. We need to be unapologetically Black in our own way without outside validation. Making Blackness a monolith, or one single overarching identity, is harmful to Black people all around the world.

Kadiatou Keita ’22