The Crescent Theater stage is a sparse apartment–a bed, scattered magazines, a fridge, an armchair, a makeshift table of stacked crates. For the two brothers, this space serves as home, although Booth reminds his older brother Lincoln that it’s just a temporary set-up–at some point, Lincoln will have to leave.

But as far as the audience of Topdog/Underdog is concerned, this intimate space represents shared and entwined lives; it is a confidential understanding of two brothers warped by shows of masculinity.

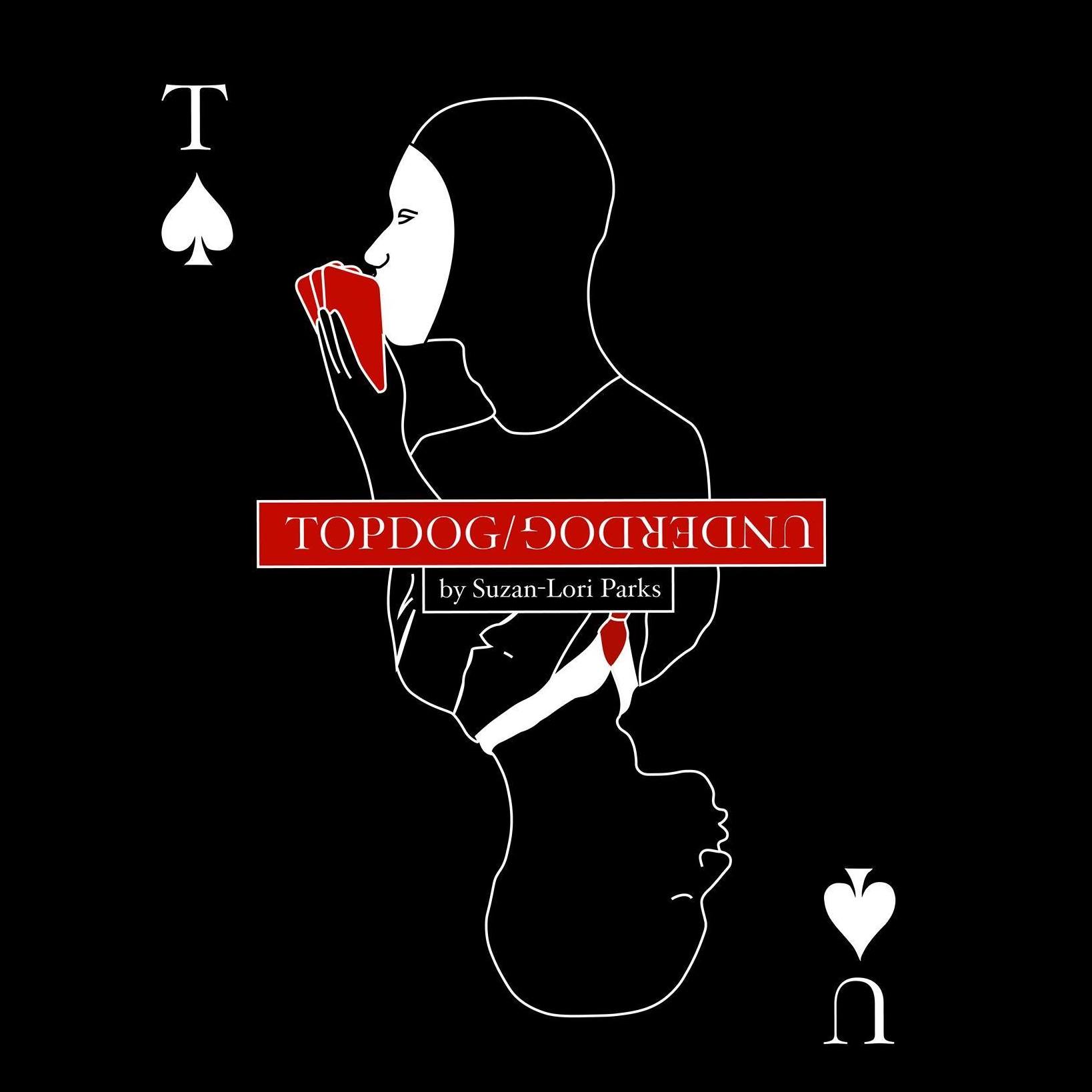

Topdog/Underdog, Suzan-Lori Parks’ 2001 Pulitzer Prize winning play, is the fall production from the Heritage Theater Ensemble, Yale’s Premier Black Undergraduate Theater Ensemble. Not unlike the filial affair on stage, the team itself is its own intimate unit. “Because of the size of this group, we became a family really fast,” Director a.k. payne (BK ‘19) tells me.The dynamic work ethic of the production team–Producer Sabine Decatur TC ‘18, Lighting Designer Prisca Dognon SM ‘20, Stage Manager Gabi Coloma BK ‘19, Props Designer Haja Kamara SM ‘19, Assistant Directors Mpiira Tabuti SM ‘21 and Rayo Oyeyemi BK ‘20, and Graphic Designer Jordan Boudreau MC ‘19–was evident in the success of the fluid storytelling onstage.

The focus onstage, of course, being the two brothers: Lincoln (Kezie Nwachukwu, ES ‘20) and Booth (Sekou Conde, DC ‘21). The tension between the two is palpable in every scene–even when they are apart, or do not share the stage, their rivalry is apparent. Be it confessions of interpersonal strife to competitive shows of three card monte, Kezie and Sekou bring full dedication to each other, as actors and as brothers.

At one point, the younger brother tells Lincoln, “Don’t be calling me Booth no more,” insisting to instead be called Three-Card, as if this new name would allow him the chance to rid himself of the burden of his name — Booth–and his status–Lincoln’s kid brother.

But no matter what Booth and Lincoln do to escape their respective past and current experiences, neither can escape the toxic masculinity that shapes and defines their every interaction.

“[Audience members] should think about the significance of women who are referenced and talked about and around in this play, but are never actually seen or heard,” a.k. says. “They should [also] think about the ‘crimes’ committed, and about the definition of ‘hustle’. How does our justice system criminalize and stigmatize in ways that impose a violent double standard?”

This active questioning is a part of the heart of the Heritage Theater Ensemble’s mission of political and personal awareness of Black lives and histories.

“I believe that freedom exists in creating our own, independent, artistic spaces,” a.k. tells me. “It exists in knowing that we are great, and that our greatness or lack thereof is not yoked to our proximity to the metaphor of “whiteness” that has been used to dehumanize us for centuries. To me, Black Theatre means the creation of rehearsal rooms, communities, and texts that are made for and by Black and Brown bodies for the purpose of generating communal sites for imagining our liberation… At Yale, Black theatre makes room for a space that is not only about production, but about creating community… Getting to rehearse in the Afro-American Cultural Center allowed us to place ourselves within the legacy of our community.”

In this celebration of Black Theatre’s legacy and inheritance at large and at Yale, the audience too must own up to the act of being an audience member, a witness to this demonstration of history and memory. Do we, as spectators, own up to our own dark, and sometimes twisted, pasts?

Topdog/Underdog will be performed at the Morse/Stiles Crescent Theatre from October 26 to October 28. More information about the cast and crew of this production (as well as performance times and tickets) can be found here.

Marina Tinone, SM’20 (marina.tinone@yale.edu)