by Alejandra Padín-Dujon

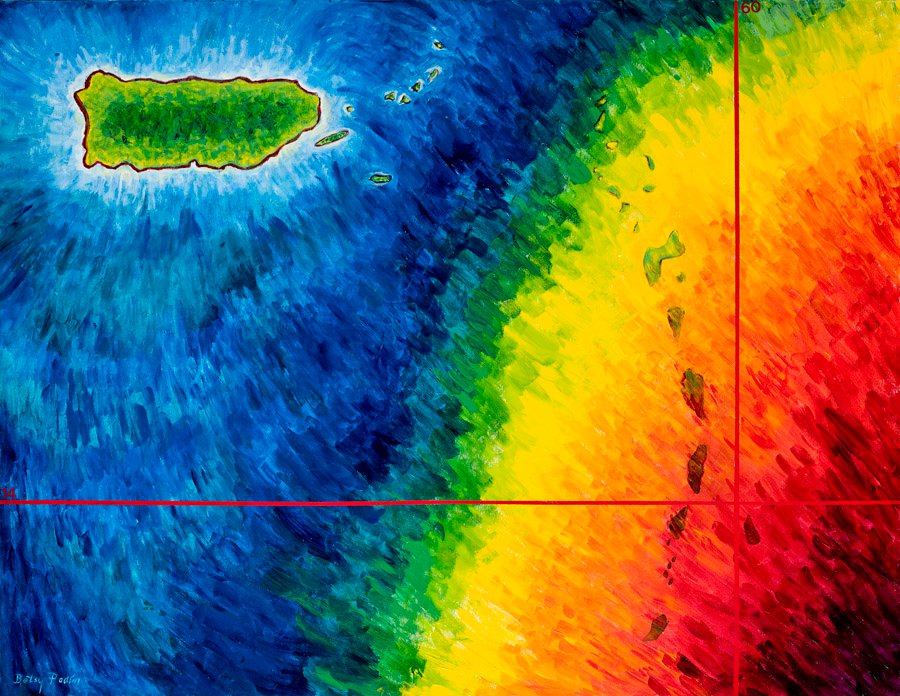

Betsy Padín,“Tormenta Anunciada (de la serie Coordenadas).” Acrylic on canvas, 46″ x 60″, 2007.

I feel vaguely uncomfortable as I sit on a bright couch at La Casa one cold, sunny Saturday, waiting to go on the inaugural Social Justice Tour of Fair Haven with a handful of other students, a local alderman, and an activist. Even my excitement makes me uneasy. I’m wary of the tour’s presumption that I am connected to all Latinos before we’ve even met—that our census checkbox dissolves differences of history, language, race, citizenship, and class. I’ve never wanted to be divisive. Yet moments before we hop on the bus, I turn to Sebi, Amanda, and the others to confess a sentiment that has crystallized inside me since my arrival at Yale: this rosy rhetoric of unity is not my Latinidad.

Before you call me Latina, I want you to know who I am.

I am a mixed-race Black, white, South Asian, and possibly taína Indian woman born to two Caribbean parents. My brother is named Ismael after the legendary Puerto Rican salsero Ismael Rivera, and his Muslim name—along with my surname Padín, from Galicia, in Spain—reminds my family that cultural exchange and racial mixture was a fact of life in Iberia long before my ancestors were shipped to the New World. The history of colonialism in my family runs deep: my mother’s island switched hands between the French and British 17 times, and less than a decade after Americans snatched Puerto Rico from the Spanish, my great-grandfather Emiliano Padín graduated from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania—enrolled as a member of the make-believe “Porto Rican tribe.”

I grew up calling beans frijoles at my West Coast public school and the Caribbean word habichuelas at home, just as I code-switched between paleta and paico, helado and mantecado, or serpiente and culebra. I read García Márquez classics until I internalized a self-conscious, academic register of Spanish. It wasn’t until my second year at Yale—removed from Spanish class and closer than ever to Puerto Rico, or Borinquen—that I finally grew comfortable swallowing the last syllable of every word, blurring R’s and L’s, and treating S’s as optional, in easy imitation of the accents that fed me growing up and still sounded like warm honey.

I identify most frequently as pan-Caribbean out of respect for both my parents and a desperate desire for shorthand to convey my Blackness, my curried fish, my French and Spanish, and my postcoloniality. After Caribbean, I say Boricua. It feels like erasure to call myself Latina first because the term is void of specificity. In cultural terms, a Latino is a racially ambiguous citizen of a country that doesn’t exist.

Latinidad serves as a cover for the extreme inequalities and diverse experiences contained within our community. The term Latino—or Latinx—does not distinguish between a Miami-born white Cuban man and a mixed-race, undocumented Black indigenous Colombian woman. It doesn’t mention the politics of language that strain our community, or how difficult it can be to carve out legitimacy as queer Catholics, non-Christians, members of an African diaspora facing racism on two fronts, or even speakers of Portuguese. The cane-sugar-sweet rhetoric of pan-Latinidad pressures us to adopt decontextualized identities that undermine personal experience and intensify toxic politics of authenticity as we learn to covet Spanish, bachata, and mestizaje all at once. Most egregiously, it masks and sustains oppression along class, race, gender, documentation, and sexual orientation lines.

Pan-Latinidad doesn’t work. But ironically enough, I found my alternative that Saturday in Fair Haven.

In a way, the Social Justice Tour was exactly right—not because all Latinos have some common essence, but because our necessarily politicized solidarity and the friction, recognition of difference, and cross-cultural understanding that goes into constructing it are precisely what Latinidad is all about.

We need to show up for each other not because we are one, but because even within our community, each of us is still Other. We need to put in the social and intellectual work to understand our prójimo, our vizinho, our neighbor—and organize to demand that Yale support us—because our bonds are born of joyful yet politically necessary and intentional love, not common experience. Possibly the only common knowledge we have is that essentialist tropes—all essentialist tropes—will ultimately fail us.

My own experience tells me that Latinidad as a tool of anticolonial resistance can’t be based purely on indigenous claims to the land any more than it can be predicated on whiteness, because Afro-Latinos—just like African-Americans—are not originally of this soil. We were shipped to this “New World” with the colonizing white settlers. We have indeterminate roots.

Latinidad is not easy. It’s not always loving. It’s not automatic. Our ability to organize and socialize around a common identity is a function of our commitment to letting different cultures and life experiences rub up against each other—sometimes painfully so. It’s our self-aware acknowledgements of difference, and our devout pledges of solidarity. Latinidad may be our birthright and a precious gift, but it’s not free. The Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata once famously said, “La tierra es de quien la trabaja,” or, “The land belongs to he who works it.” This may not be Mexico, and ours may not be that kind of revolution, but a similar principle still applies: just entitlement is an oxymoron. There is no community without work.