In the months leading up to the Women’s March on Washington, Native women leaders across the Nation came together to form a collective called “Indigenous Women Rise.” The name originates from a hashtag representing the resiliency of Indigenous women and notably used by women leading the No DAPL movement.

The Indigenous Women Rise collective organized a rally for Indigenous women in Washington, D.C. the morning of the Women’s March on January 21. Indigenous women joined together to share stories, sing, and pray before the Women’s March began. The rally included speakers such as Deborah Parker, a well-known Tulalip leader who worked to pass the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) which restored the jurisdictional power of Native nations to persecute non-Native abusers, and Caleen Sisk, the well-known spiritual leader and Chief of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe.

At women’s marches across the Americas, Indigenous women united around a design created by Apsaalooke and Northern Cheyenne designer B. Yellowtail and artist John Isaiah Pepion. The design features the Apsaalooke Aláchiweelissuua, a victory dance known as the “Shoshone warbonnet dance.” Called the “Woman Warrior” design, Apsaalooke women in elk-tooth dresses and headdresses are represented as simplified, stylistic figures forming a circle.

“I felt it was important to design the artwork in the form of a circle because of our value systems,” Yellowtail explained in an interview with the L.A. Times. “And the way we think of life is always in a circle. It is not linear.”

Through the Aláchiweelissuua, the Apsaalooke community honors both veterans and the women who the veteran’s select to dance. Being chosen to dance is one of the highest honors an Apsaalooke woman can receive and one of the only instances in which an Apsaalooke woman will wear a headdress. Yellowtail’s design is particularly striking given the cultural importance of the dance and the identifiable significance of a headdress even to Indigenous peoples who do not use them.

In partnership with Native Americans In Philanthropy (NAP), Yellowtail created turquoise scarves featuring the “Woman Warrior” design that the Indigenous Women Rise collective handed out leading up to the rally. Accordingly, the collective asked Indigenous women to wear turquoise scarves, shawls, and jackets. During the Women’s March, a distinct group of an estimated 300 Indigenous women walked along the route. Some women wore their best beaded earrings and others showed off their turquoise jewelry. Women wore ribbon skirts or traditional regalia or t-shirts emblazoned with “#NoDAPL”.

Although I didn’t have the opportunity to march with the Indigenous Women Rise group, I deeply appreciate the Indigenous female leaders who created space for Indigenous issues at the Women’s March. I decided to attend the Women’s March before the group had formed. After Indigenous women took to social media to spread the word about the Indigenous Women Rise collective, I felt more reassured that attending the March would be productive as an Indigenous woman. The women unapologetically embraced and celebrated Indigeneity. Along the route, Indigenous women joined in chanting “Mni Wiconi” and held signs condemning Native police brutality and violence against Native women.

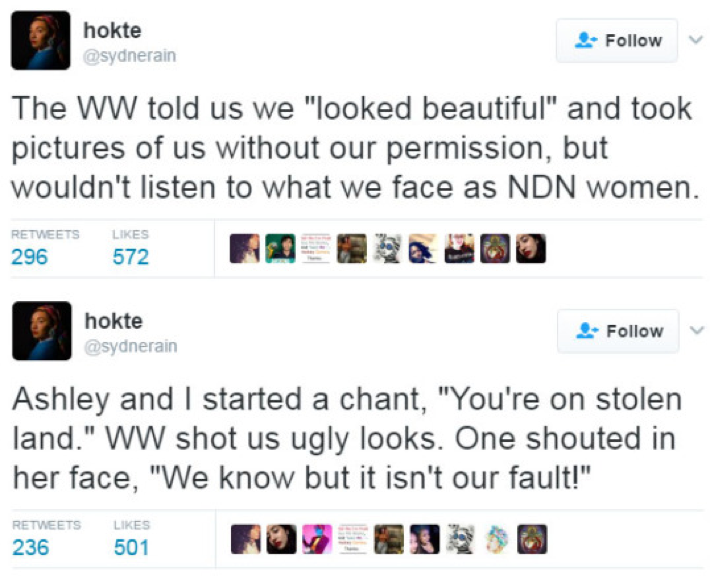

Several Indigenous women Tweeted instances of non-Native women aggressively approaching the group. Hokte, from the Mvskoke Creek Nation, tweeted a thread detailing her experiences at the Women’s March and interactions with white women. She says that white women ignored and “mocked” her and the Indigenous women walking alongside her. One white woman even told her friend “I guess we’re Indians today,” when they realized they were surrounded by Indigenous women.

Hokte is not the only woman to speak up using social media about her experiences at the Women’s march. Nambe Pueblo woman Debbie Reese tweeted her reluctance to attend the March and subsequent disappointment upon seeing signs erasing Indigeneity such as “We are all immigrants.” Indigenous women also reported seeing March participants flaunting Washington football team gear.

Although several Indigenous women spoke during the Women’s March on Washington rally, the views held by many Indigenous women and issues concerning Indigenous women were rarely represented on signs or in chants outside of the Indigenous Women Rise group. Additionally, one of the Indigenous women scheduled to speak, Comanche politician and social activist LaDonna Harris, did not have the opportunity to speak when the rally had gone over too long, according to March organizers.

Apart from this cohort of Indigenous women, I felt simultaneously disempowered and inspired. Actively turning away from certain signs and voices made me feel powerless to the anti-Indigeneity woven into the fabric of white feminism, which is predicated on exploiting Indigenous knowledge and actively benefits from settler colonialism. Yet it felt liberating to be in Washington where so many people dared to speak with clear voices and hold signs calling out the white heteropatriarchy and systematic racism.

Though space wasn’t cleared for us at the start, Indigenous women demanded space in women’s marches on January 21. Across the world, one design and saying united us against the violence of both government and protester. I chose to march in Washington because I refuse to be politically terminated by a settler colonial government and be stripped of our Indigenous sovereign rights to protect our peoples and lands. I know we have the strength of our ancestors and the guidance of matrilineal societies to traverse this political landscape. Our resistance is a story told and retold again: Indigenous women rise.