by Janis Jin

A white boy walks clumsily onstage with a backpack slung over his shoulder. His awkwardness is carefully constructed and his shy smile is too intentional; this white boy could only be a certain type of white boy (we all know the type). He turns to the audience and begins, “I wanted to start by saying…thank you.”

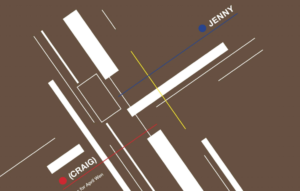

And with these words, we are whisked into the world of April Wen’s Jenny (Craig).

As Craig (Alec Mukamal ’18) begins his presentation, we become his classmates in an African American history class at a New York City high school. Craig begins a conversation about Race in the United States by pulling out a puppet, named Lance, in a police uniform from his backpack. The two begin to talk to one another. Craig figures himself as the “good” white man. He offers a history of miscegenation to Lance, who is racist but well-meaning (quite like your racist white uncle, perhaps) and also happens to be married to an imaginary Chinese-American woman puppet, Ling-Ling. But as Craig’s voice takes on two different personas, we become aware that the gap between the characters is perhaps not that great.

Craig’s biracial Black girlfriend, Jenny (Olivia Klevron ’18), sits with us in the front row of the audience. We watch Craig and Lance. We watch Jenny watching Craig and Lance. And a television at the back of the room makes us wonder who might be watching us.

To portray Jenny (Craig) in a linear or streamlined narrative feels like an injustice to the play’s insistence on meanings that are intentionally hazy, characters who bleed into each other, time that passes but never moves forward. Director Gregory Ng ’18 smiles when I say that I feel like there is a lot I don’t understand about the end of the play. I tell him that I still have a lot of unresolved questions. “I think in many ways April means for this play to generate more questions than answers,” he tells me.

April Wen ’17, the creative force behind Jenny (Craig), says that she draws inspiration from theater that unapologetically foregrounds race as the fundamental conflict in the story. “As an audience member, I have found myself witnessing such ‘race plays’ unfold to show pain and violence on the body, the mind, and the two inseparably,” she says. “For those who do not experience racial trauma in their lives outside the theater, this unfolding reveals something. But for everyone else, it can have the effect of reiterating a pain that we have known, continue to know, and must know all the time.”

Race unfolds in Jenny (Craig) through surveillance and the racial imagination, in various modes of experimental transmedia performance. A television and surveillance camera play central roles throughout the plot, and even when they don’t, their presence always haunts the scene. Ng says, “For me, this play gestures at the kinds of surveillance we take part in when we watch bodies onstage, onscreen, and off. What kind of television and surveillance do we use in order to turn people into raced subjects for our consumption?”

As Jenny and Craig delve further into their relationship, Jenny becomes increasingly aware of the ways she is being watched – in the classroom, in her bedroom, on the street. She notices the slippage between Craig and the forms of racial surveillance he insistently attempts to distance himself from. As Jenny is forced to grapple with this in the space of her mind, she creates a Chinese-American alter-ego named Bibbe (Stefani Kuo ’17). The imaginary friendship between them becomes Jenny’s only sense of freedom in a world in which the racialized body is constantly under surveillance. Olivia Klevron is captivating as Jenny, giving both the fire and the innocence of a biracial Black 17-year-old beginning to realize the ways she is being watched by the state – and her own boyfriend – and refusing to become an object under surveillance.

It is the space of the imagination that offers radical modes of intervention throughout the play. At one point, Bibbe picks up Lance, Craig’s police-puppet, and begins to use him. She takes on the voice of Ling-Ling, Lance’s puppet-wife, who only previously comes up as a silent figure during Lance and Craig’s discussion of miscegenation. When Bibbe picks up Lance and begins to speak as Ling-Ling, the figure of the Oriental wife is suddenly an insurgent voice. Jenny and Bibbe sit side-by-side as the scene plays out, laughing and tossing Lance around as Craig is asleep. And as Jenny and Bibbe’s friendship permeates the world of Jenny (Craig), we are given a points of departure for thinking about the possibilities of Black-Asian racial coalition.

“I wrote Jenny (Craig) because of friendship,” Wen says. “That experience enfolds another, of being racialized in America. But given the history and forever tense presence of race – be it between individuals, between histories, between bodies, and within the singular body – people who are racialized against whiteness have to contend with race. We were never given a choice not to. What I can do, as a writer, is to start with a text that takes us somewhere new. The imagination, I think, can be that new place – a home that is jubilant, exploratory, unapologetic.”

Jenny (Craig) unapologetically opens up the possibilities of resistance in the imagination. Jenny and Bibbe ask us what coalitions are capable of being built in an alternate space, one in which race is not predicated on the presence of whiteness and its surveillance of the racial imagination. The play is striking for its experimental nature and the fusion of various forms of media performance. It undoubtedly feels like the “new place” that Wen wanted to create. But Wen herself puts it best: “The specificity of Jenny (Craig) may be its “newness”. But at the same time, the imagination is a resilience that for people of color in America, is quite beautiful, and familiar news.”