“1-We are the people! 2-You can’t divide us! 3-We will not let you build this pipeline!” This chant echoed off the Bank of America, ringing out across downtown New Haven Friday evening as demonstrators assembled in opposition to President Trump’s recent Executive Order expediting the construction of the Keystone and Dakota Access Pipelines.

The event, organized by journalist Melinda Tuhus and activist Norman Clement, called for New Haven citizens to remove their money from TD Bank, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. These banks help fund the Dakota Access Pipeline: a 1,172-mile long oil vessel that would transport its contents from the Bakken/Three Funds area of North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois. Critics of the pipeline point out that it threatens the drinking water of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North Dakota and its construction has already destroyed several of the tribe’s sacred sites.

The Facebook event for the demonstration, titled, “March to Stop Trump’s Plan to Fast Track DAPL” included a description calling for solidarity with other groups and causes vulnerable to the policies of the Trump Administration, including, “immigrants, women, LGBTQ folks, black lives, low-wage workers and the climate.” The event was advertised through the Facebook group CT Stands with Standing Rock. As supporters gathered outside Wells Fargo around 5:30pm, Tuhus read aloud the action agreements of the demonstration while passing drivers honked their horns in solidarity.

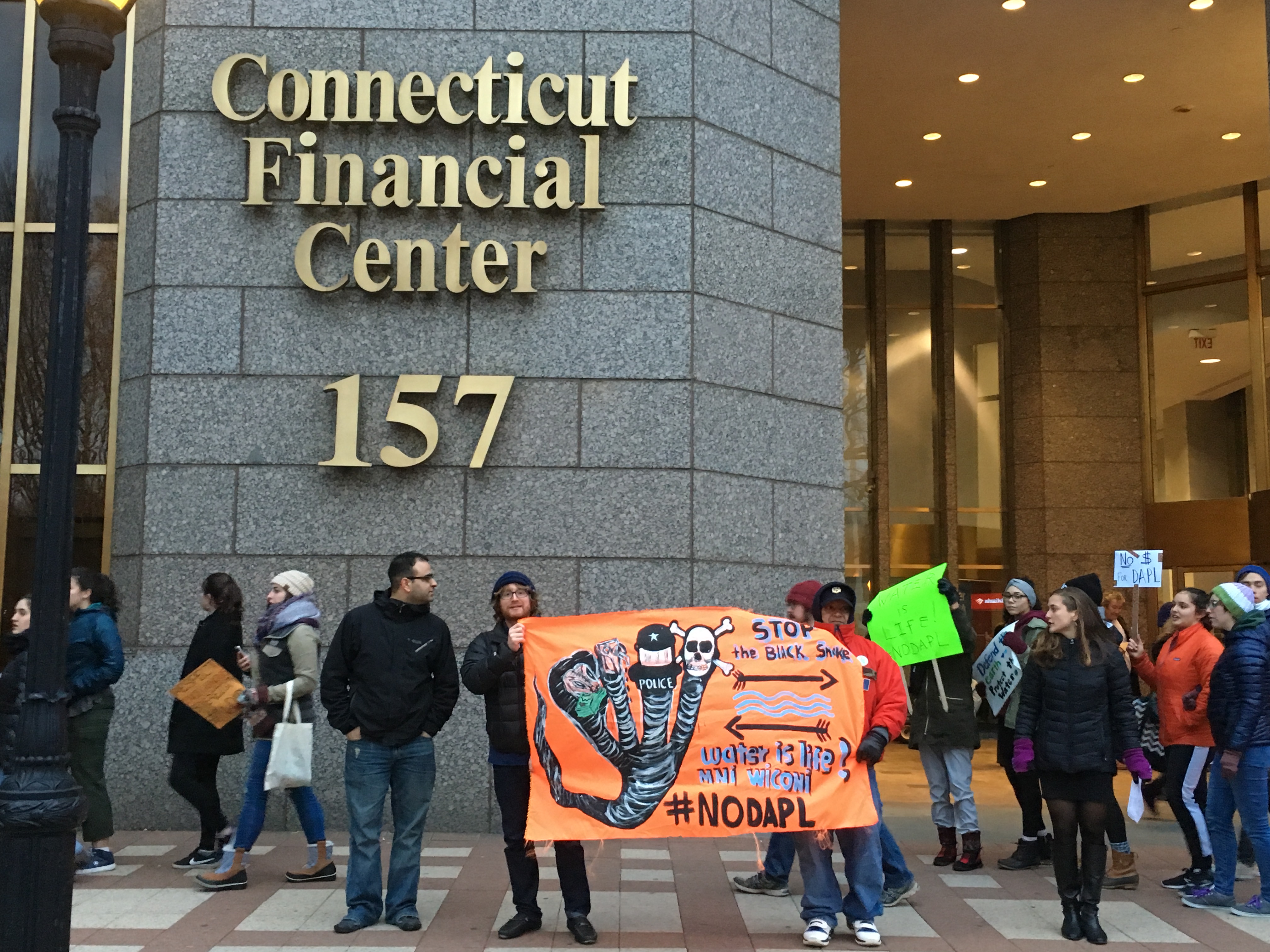

“We will be nonviolent. We will maintain an attitude of openness, discipline, and respect toward everyone we encounter. We will not destroy or damage any property. We will not carry or use weapons. We will respect Native peoples and traditions. Non-native allies, this means no imitation or appropriation. We will all take personal responsibility for our own actions. Can I get a yes on that?” Tuhus asked. The crowd responded with a cheer. Over the next two hours, the demonstrators marched from Wells Fargo to Bank of America, and finally to TD Bank where the crowd occupied the TD Bank lobby.

Tuhus, a New Haven resident who has been practicing independent journalism for 25 years, attributed her passion for this cause to personal relationships with Lakota activists. When asked over email what motivates her to engage in this form of activism, she replied, “I knew some of the folks at the second battle of Wounded Knee in 1973, and the terrible irony of the U.S. Army (Corps of Engineers) inflicting yet another atrocity on this same native nation led me to get involved in the fight to stop DAPL.”

Following the acceptance of the action agreements, co-host Norman Clement spoke into a megaphone and urged demonstrators to remember that their activism was taking place on the ancestral land of the Quinnipiac people. “We’re standing on Quinnipiac tribal land, and we must always be conscious of that…the Quinnipiac tribal people gave their lands so we can be here today. Let’s always remember our ancestors,” he said, eliciting cheers from the crowd.

Native students from Yale University were also in attendance, and several students represented their tribal nations during the march. Paige Johnson,‘20, unfurled the banner of the Blackfeet Tribal Nation under the Bank of America. Andy DeGuglielmo,‘18, of the Sault St. Marie band of Chippewa Indians, marched with his tribal flag wrapped around his shoulders. Outside the Bank of America, DeGuglielmo stepped forward and urged the crowd to remember that tribal sovereignty, in addition to the environment, is under dire threat from the Trump Administration and the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“When we disregard the rights of marginalized people we diminish their humanity, and the subsequent exploitation can no longer be tolerated. We’ve been fighting for 300 years; we will continue fighting for as long as this takes, but we need to stand up and fight for tribal sovereignty above all else,” DeGuglielmo declared.

Several demonstrators held signs that read “Honor the Treaties”, a reference to the fact that the United States has violated, amended, or nullified over 500 treaties made with American Indian nations. These treaties carry a weight similar to treaties made with foreign nations. In 1831, the Supreme Court ruled that Indian nations have a limited form of sovereignty as “domestic dependent nations,” and that the relationship between Indian nations and the Federal government is essentially that of “a ward to his guardian.” Indian treaties were made from 1774 until 1871, when the US government passed the Indian Appropriations Act. This act prohibited further treaty-making with Indian nations, but held that existing treaties would still be honored.

The Trump Administration has signaled that it intends to privatize Native lands in order to open up deregulated drilling opportunities. Such a political move evokes memories of the Dawes Act of 1887. The Act replaced traditional systems of communal land ownership with colonial concepts of private property by breaking up reservation systems and allotting lands of uniform size to tribal members. Extra lands left over from allotment were made available for purchase by non-Natives. Consequently, Native peoples lost much of their ancestral lands. This system ended after the passing of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, and the reservation system continues to protect Native lands for tribal use. The Trump Administration’s approach to Indian affairs would greatly diminish tribal self-determination, and it represents a radically new direction in US Indian policy that threatens the sovereignty of Native nations across the country.

While the future of tribal sovereignty remains uncertain, demonstrations such as Friday’s suggest that public support for Native issues is at an all-time high, and the public will no longer tolerate the continued marginalization of Indigenous peoples in America.