by Ahmed Elbenni (Contributing Writer)

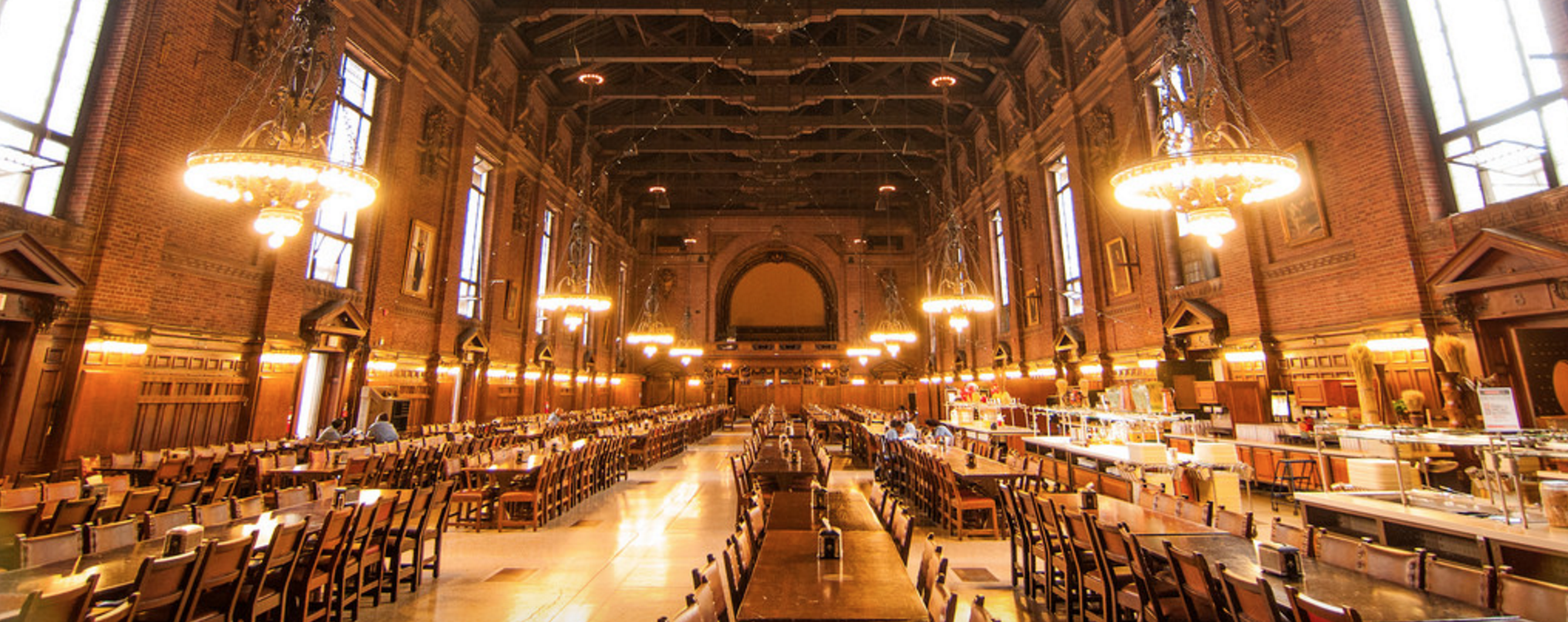

Something profound happened last Tuesday, during the Eid banquet. That night, standing before a crowd of over five hundred Muslims, Christians, Jews, agnostics, and atheists under a portrait of George H. W. Bush in the largest dining hall of my secular university, I recited verses from the Quran, the Islamic holy book. Students, professors, and administrators all listened in silence as the words of God reverberated off the hallowed halls of Commons. In that moment, and in every moment of the following two hours, I could not help but marvel at the sheer improbability of the Eid Banquet.

Hosted annually by the Muslim Students Association (MSA) and the Chaplain’s Office, the Eid Banquet celebrates Eid al-Adha, one of two major Islamic holidays. One of these holidays, Eid al-Fitr, celebrates the conclusion of the holy month of Ramadan while Eid Al-Adha celebrates the conclusion of Hajj. The Hajj is a holy pilgrimage undertaken annually by millions of Muslims in the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina.

Eid al-Adha’s celebration of Hajj reflects its larger thematic focus on the Prophet Ibrahim. Many of the rituals performed throughout the holy pilgrimage originate from the acts of devotion demonstrated by Ibrahim and his family when subjected to a series of trials by God. Ibrahim, whom Muslims call the “father of the Prophets,” is a major figure in Islam, as the religion represents the fulfillment of the monotheistic message he preached: submission to one God alone. The importance of Ibrahim’s legacy is reflected in the significance of the holiday. The Eid Banquet is just one way of acknowledging that.

Like the country flags drooping limply from their positions on the walls of Commons, though, an air of wistfulness hung over the proceedings. For many, including myself, the 15th Annual Eid Banquet will be the last they’ll experience during their time at Yale. Commons will be closed for the renovations of the Schwarzman Center for the next three years, and will not reopen until after the current Muslim upperclassmen have graduated. In addition, Common’s temporary unavailability will coincide with Eid’s shift to the summer, a phenomenon possible courtesy of the Islamic calendar’s adherence to the lunar cycle. As such, the Eid Banquet in its current form will not exist again for a long time. Despite this, Muslim Chaplain Omer Bajwa is hopeful that the banquet can be rebooted under a different name once Commons returns.

Even when accounting for the poisonous political climate of the past year, the banquet arrived at an especially sensitive time. Following the New York bombings last Saturday night, Islam had dominated the media cycle as it too often does when terrorism is conflated with the religion. The unfortunate incident provided a somber backdrop to the banquet that even its festive tone could not conceal.

Even while the current challenges facing Muslims clearly weighed on the minds of the speakers, they did not allow themselves to be dragged down into the bottomless pits of negativity. Instead, they framed the event as a proud rebuttal to the Islamophobic intolerance that characterizes the nation’s political mood.

“These are not the easiest times to be Muslim,” President Peter Salovey acknowledged in his address. “But when I look out at this tradition at Yale University, I realize…that the way in which there is mutual respect and inclusion at Yale is different, and that Yale University in that way, perhaps we can say with proper humility, is a model for the rest of the country and maybe the rest of the world.”

Initially, President Salovey’s words struck me as overly ambitious. Yet as I gazed around the overstuffed hall and took in the dizzying array of races, ethnicities, and religions that gazed back in the forms of my peer and professors, all of whom were attending an explicitly Muslim-themed event, I could not help but acknowledge the kernel of truth they possessed. It seemed hard to believe that such a beautiful display of tolerance and compassion was taking place on the same campus that had been torn apart by the controversies of intolerance and indifference just a year ago.

Such thoughts seemed to have occurred to Dean Jonathan Holloway as well, as he referred to the painful events of last fall while lamenting the forces that seem intent on provoking hostilities in the present. Ultimately, the Dean chose to focus the brunt of his speech on what the Eid Banquet symbolized to a university healing from its wounds and moving forward.

“Look around you,” he said. “Look with your soul. Recognize the transcendent beauty of this event, of your friendships, of your desire to demonstrate that you believe in a loving community, one that can survive the weak attempts to tear it apart, one that can have hurtful disagreements, certainly, but one that at its core recognizes everyone’s fundamental humanity.”

Such optimistic themes underlined the evening and repeatedly came to the forefront. From the heartfelt reflections of Nazar Chowdhury ’20 and Daad Sharfi ‘17 to the keynote address given by Shawkat Toorawa, a new professor in the Near Eastern Studies department, all the speakers spoke to the gratitude they feel towards those who have supported them in the past and their hopes for a more tolerant future.

Abrar Omeish ’18, the president of the MSA, put best what the event represents for the Muslim community.

“I find it to be a tremendous stand against the vitriol and hate that is surrounding us right now,” Omeish said. “The people attending represent the support that is out there for us [Muslims] and is a good reminder because we often feel…that people aren’t aware of what we’re facing.”

I savored every moment of my second, but last, Eid Banquet, from the delicious food served by the amazing dining hall staff to the multilingual music playing over the animated chatter permeating Commons. After catching up with friends and posing for pictures, though, I knew it was time to go. My homework assignments weren’t going to complete themselves.

As I prepared to walk out, I took one last glance at the spectacle of the event. It struck me how similar Yale’s initiative for achieving tolerance is to Islam’s message of egalitarianism. In many ways, the Banquet captures the dual universalism that lies at the heart of modern Yale and Islam, constituting an elegant union between the secular and the divine. Dean Holloway’s words that evening had never felt truer.

“This is a beautiful thing, and I want to applaud all of you for your commitment to this beauty.”