by Eleanor Pritchett

The little pink magic marker in my hand seems too light for the heaviness of the task in front of me.

Draw a moment when you’ve felt unsafe.

Suddenly I can’t think. This room in the New Haven Public Library full of young queer and trans* New Haveners is such a safe space—where are the unsafe spaces? I have to fight to remember sometime this month when I, a queer woman of color, felt unsafe.

That’s the power of the New Haven LGBTQ+ Youth Kickback, and of the LGBTQ+ Speak Out (#SpeakforYrself).

Safety — Housing — Jobs.

These are the necessities that queer and trans* youth lack most disproportionately. You’ll hear these words repeated constantly in queer activist spaces, and Kickback is here to give them the space to come to the forefront.

In a moment, one of the chief organizers will take the stage and introduce themselves and the rest of the organizers, but for now the room is abuzz with recognition and curiosity. “I’m so happy to see you!” muffled through the barrier of a tight hug; introductions between seatmates and reunions of old acquaintances.

Under every seat is a small square of posterboard, a marker, and a triangle of construction paper, which we will use later to create a big collaborative art piece with the People’s Arts Collective of New Haven about our own experiences.

There are two boards on the stage: one says “WELCOME!” in big, happy letters and lists the schedule for the 2 hour event: introductions, feature stories, Art Part, and, of course, stories by the youth of the audience. The other says the themes of the day in thick black bubble letters over pastel drawings of happy smiling faces over a pastel-colored background reminiscent of a cityscape:

Safety — Housing — Jobs.

Isabel, a queer woman from New Haven, told of her experience regarding safety in the city. “Where in New Haven can I feel safe?” she asked the crowd, explaining that she felt both unsafe in the city and at war with her own self. “The silence that I learned was my own form of unsafety,” she said.

“I am white, privileged,” she told the audience. “I can’t imagine what it would be like as a trans kid of color.”

Next, Zoe told a story about her experience with homelessness in the city of New Haven. She’s tall, with a solid presence, but in telling about having to get herself out of a home in which she was told, in her words, “We don’t want you here,” she suddenly looks small.

“I left, and I had nowhere to go,” she says. When it was warm, she says, she slept outside behind a school. When it was cold, “I saw someone who looked decent, made friends, got drunk and manipulated the situation.”

“Why aren’t there places for queer youth shelters?” she wanted to know.

Another youth, Flavio, who asked that everyone refer to them with the gender-neutral pronouns they/them/theirs, told a story about jobs. In their experience, and in the experience of their parents who don’t speak English: “I am the only gateway for them to get their basic necessities,” they said. They pulled the chair off the stage so they could sit on our level. They sat legs crossed, long hair falling into their eyes. Their story is an appeal, a plea. “They’re reducing somebody to a body, to the actions they perform,” Flavio nearly spit out.

No one ever thinks of speaking out of turn here; applause is kind and enthusiastic.

After the centerpiece stories and the break to draw and reflect, the floor was opened up for anyone in the room to come up and talk about their experiences, with priority given to the young. More than half a dozen young people, most of whom attend weekly Kickback meetings where they work on opening up about their lives, shared some of their most personal stories. Even Zoe remarked that before working on the speak out and even halfway into planning it she felt self-conscious about sharing: “I don’t know if I have relevant experiences,” she remembers thinking, though, of course, she did.

The speakers told their stories about being homeless, about coming out to unwelcoming loved ones, about being queer in the military, about needing work, about feeling alone, and about feeling hopeless, and although these stories were truly heartbreaking, one sentiment rang true throughout all of them: Kickback makes the speakers feel safe.

“It’s hard for me to imagine someone who doesn’t want to do this work,” Zoe says. “It’s important for me, my wellbeing, and my life.”

Safety — Housing — Jobs.

“The way things are is not enough,” Isabel said succinctly. And, of course, it’s true: there are more than 400 self-identified homeless youth in New Haven right now, and there are, as was estimated during the speak out, maybe twenty beds for them at shelters. A new and much-praised community center, The Escape, has a shelter called The Situation, which boasts fifteen beds for boys 13 – 24 years old and no current resources for LGBTQ+ boys or beds for girls of any kind.

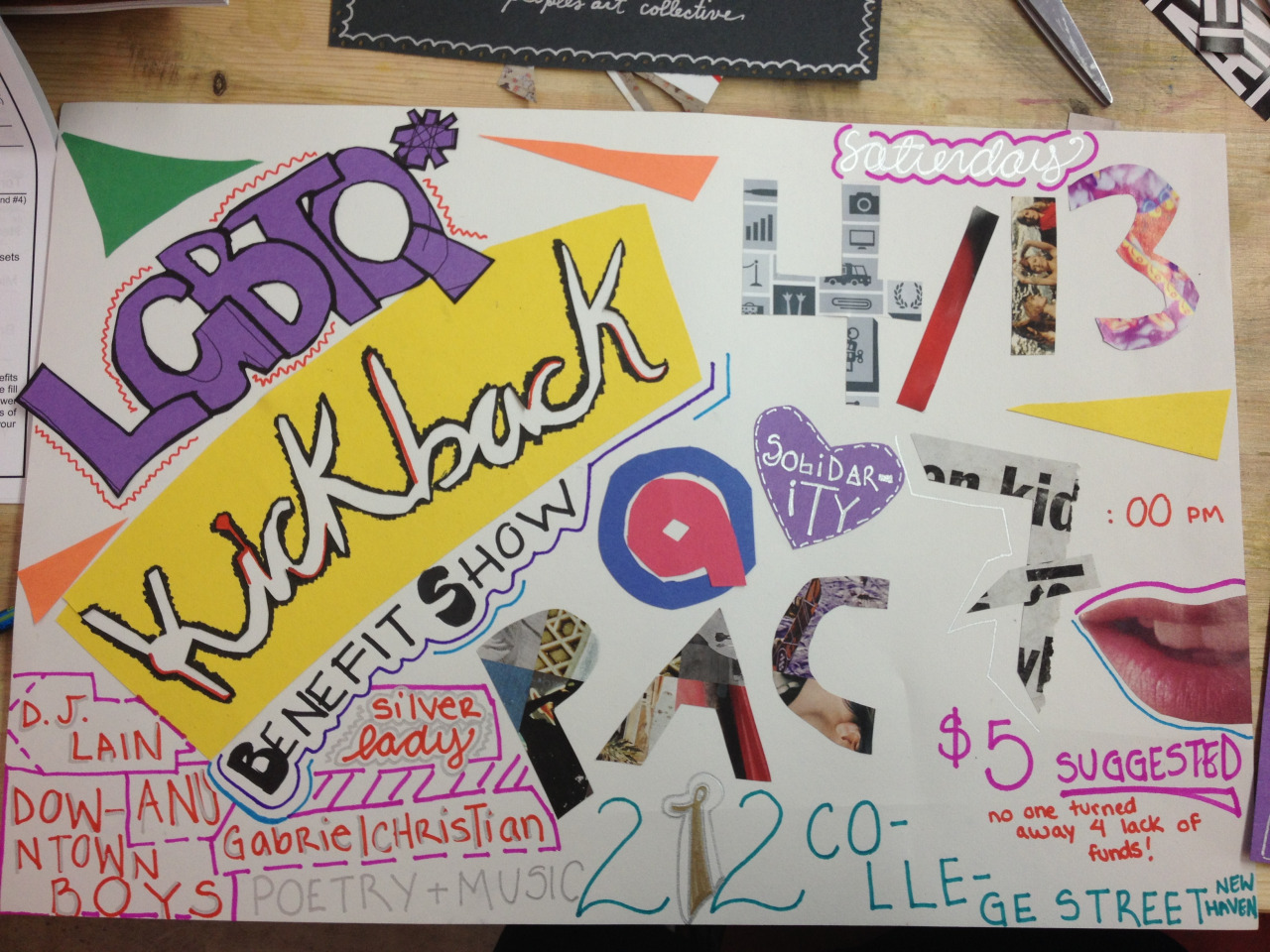

These are issues which dramatically affect the city of New Haven, and which dramatically affect its LGBTQ+ youth—and, as always, these are issues in which Yale students must make their influence count. If we don’t use our privilege as an amplifier for those voices without, we use it as a stage on which to stand above them. Kickback meets Mondays from 3:30- 6pm at the People’s Arts Collective of New Haven as a “weekly hangout space for New Haven queer youth.” Find them on Facebook as Lgbtq+ Youth Kickback or on Tumblr as lgbtqyouthkickback.tumblr.com.