by Eleanor Pritchett

We write music/ we write songs/ to tell a story,” Lin-Manuel Miranda rapped in his Grammy acceptance last week, standing on the stage of Broadway’s Richard Rodgers Theater. Pushing to the front, Anthony Ramos waved Puerto Rico’s flag, frantic and proud; behind him was the whole cast of Hamilton, the breakout rap musical Miranda wrote, directed, and now won a Grammy for.

Hamilton is the story of “America then, told by America now.” It’s told by “America now” not only in the deliberately POC casting, but in the very story itself. Lin doesn’t just play a Hamilton who happens to look Puerto Rican, he creates a journey that includes the reclamation of an immigrant identity, sacrifice, sisterhood, friendship, debates against slavery, and a fight against tyranny that can’t help but speak to POC of today.

It’s a show about people of color, by people of color—for people of color, but in true Broadway fashion, everyone who has seen this show is white.

“Do you know any people of color who’ve seen Hamilton?” Long pause. “Yeah, me neither.”

Repeat a dozen times.

From experience and from asking, I’ve found one person of color around me at Yale who has seen Hamilton. That begs a thousand questions. Why are white people so into Hamilton? Why don’t people of color see Hamilton? Who is Hamilton’s audience?

For the 2014-2015 season, nearly 80% of tickets on Broadway were bought by white people; of the audience over 25, “78% had completed college and 39% had earned a graduate degree.” Jury’s still out for the 15-16 season, but this is what Broadway is: patronized by educated white people.

This just doesn’t jive with the visceral way the show affects people of color. There is so much love for this show; it’s very moving, and it clearly moves its fans. It makes you cry and love and root for the characters and cheer at cabinet battles and somehow get emotionally involved in the sentence, “You’re gonna need congressional approval and you don’t have the votes” (I promise this is riveting as a lyric).

There has been a huge artistic response to the show: cover after cover after cover (after cover after cover), a ridiculous amount of art, and hundreds of people waiting in the cold for the $10 ticket lottery every day.

Whenever I say how much I love this show, it’s, “Oh, have you seen it?”

I always answer, “No, no one has.” Not because it’s true—of course people have seen this show if it’s making [this much money]—but because oftentimes the people who love it most haven’t seen it. For fans of the show, it’s an aspiration to be in the audience, but it’s essential to have loved it.

The fact of loving Hamilton is that the show is only marginally longer than the cast recording, which has been up on YouTube and Spotify since October. There are very few unsung scenes, which makes it accessible and easy to love if you’ve given up the 2 hours and 22 minutes. And fans of the show are often teenagers and young people, who don’t tend to have the resources to leave YouTube or Spotify due to the fact that the show has been sold out through 2016, and tickets tend to be on the secondary market for hundreds or thousands of dollars.

This is the tension between the fanbase and the audience of the show. Hamilton tickets have been bought in bulk and sold on the secondary market while the fans waiting outside know all the words to the show to sing along during Ham4Ham singalongs.

Clearly these are true fans of the show who have a huge desire to be a part of the audience, but they are quite literally being left out in the cold.

You have to draw the line somewhere in order to make money–and, for Lin Miranda, to create a phenomenon that pushes people of color to the front of the national consciousness through Broadway of all venues is an incredible, and very profitable feat. However, knowing that the voices on the cast recording are of color is not the same as seeing people who look like you playing the heroes of your grade school history lessons.

Every day 21 front row tickets are offered in a lottery for $10 each, making the show an attainable dream for many dedicated Hamilton fans. The lottery almost always comes with a #Ham4Ham show, where Lin and the cast joke and perform in front of the waiting masses. (The lottery has recently moved online for the winter, if you’re inclined to try it from the safety of your dorm, and Lin posts daily Digital Ham4Ham videos.)

The cast and crew of this show are dohere for people of color. They’re waving PR flags at the Grammys. They’re correcting “nice racists,” like the NPR reporters who say the show has a “minority cast.” “The casting is not ‘minority.’ Your piece is going to be dated in about five years when we’re the majority. So you might want to say ‘people of color,’” Lin practically spat.

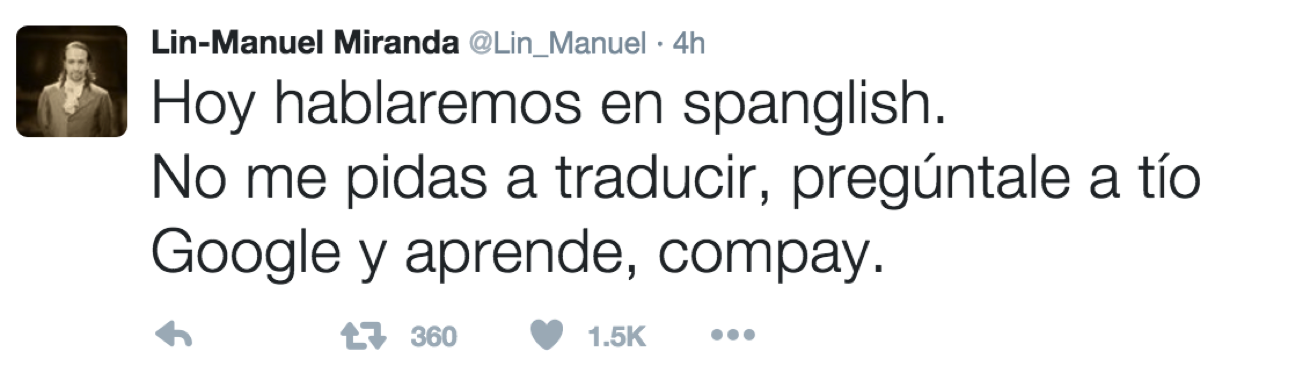

They’re uploading the cast recording on YouTube right as the show goes on Broadway. This year they’re instituting Wednesday matinees specially to bring in schoolchildren from New York and New Jersey. As I’m writing this article, Lin is spending the day only tweeting in Spanish, not for any particular reason, and with no preamble but this:

It’s an attempt by the show to be part of the audience that’s mistreated by the medium at the same time as it exists as part of Broadway. It’s odd and unfair and bizarre in that a 80% white, 80% educated group should be the in-person audience for the revolution that is Hamilton, but it’s fascinating and brilliant that the show allows those disenfranchised others to be its real fans.

In Lin’s words, “I’m sorry theater only exists in one place at a time but that is also its magic.” The revolution lies in the claim that people around the world with no way to be in that room have to an event that only exists on 46th Street.