by Ishrat Mannan

In 2011 the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Jason Kenney who is currently Canada’s Minister of National Defense and Multiculturalism, introduced the ban on niqabs, a piece of cloth used to cover a Muslim woman’s face. Kenney along with the past Prime Minister of Stephen Harper justified the ban by claiming that it “protects women from violence” and that the women who wear them are “offensive.” In one broad stroke, the legislation passed sweeping generalizations of violence being uniquely inherent to a religious community while vilifying women who make the choice to wear a niqab.

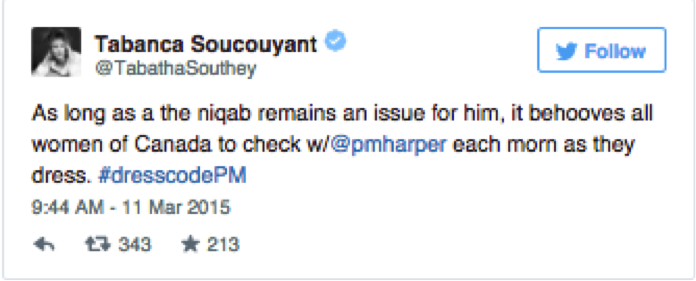

The misogynistic focus and desire to control Canadian women’s clothing has prompted the mocking of the conservative government from Twitter.

Twitter, however, also became a space to spark a different conversation with this ban and Muslim women in mind. Inuit women created a hashtag “#DoIMatterNow which involved putting on makeshift niqabs to draw attention to the systematic disenfranchisement of Native people and to express solidarity with Muslim women affected by Harper’s policy. The campaign’s manifesto explains:

“Indigenous women are fighting for the right to be safe and in control of our own bodies, and instead of launching an inquiry to uncover the systemic racism that caused an epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women, Harper attacks our Muslim sisters for what they choose to wear. … PM Harper, it’s my body, my clothing, and MY decision. You will not distract me from issues that actually matter to me as a Canadian. In solidarity with our Muslim sisters.”

When Harper was asked to draw greater attention to the plight of missing and murdered indigenous women (MMIW) he responded by claiming that “most of these murders, sad as they are, are in fact solved.” This statement starkly contrasts with a 2014 RCMP report that says 1,107 Aboriginal women were murdered and another 164 went missing between 1980 and 2012, and of those cases 106 murder and 98 missing cases are unsolved.” The sheer disproportionality of MMIW rates are not unique to Canada, the US has rates that more than 1 in 3 Native women will face sexual assault. These rates do not appear, they are the result and process of centuries of discrimination.

This campaign within the Twitter-sphere is the manifested desire to shift the national and media attention surrounding Canadian women.

Besides being able to highlight Indigenous and Muslim women’s oppression under both systematic and political structures, this particular campaign also tries to draw both of these issues into the same conversation. Drawing visibility to a community’s’ pain is a tiring ask because it forces people to plea for their humanity in the same breath. To ask you to care.

These two communities, while ultimately seeking justice, are aiming for different responses from the Canadian government and society. Muslim women are calling for loyalty, citizenship, and freedom to dress how they choose to and not be under attack by a patriarchal society while Indigenous women are asking for a more responsible and active state engagement in aiding their community with gender biased violence.

The distinct goals of these two communities does not limit the opportunity for solidarity. Acts of solidarity must work to further the causes of a community and this particular campaign was a wonderful example of the manner in which other communities’ struggles can and should be addressed by all. We should ask ourselves how acts of solidarity should echo the voices, causes, and goals of the group that are in need of support.