by Holly Chung

The Graduate Employees and Students Organization (GESO) is used to opposition from Yale’s top administrators, who don’t want to negotiate with yet another labor union. But recent public criticism among its own constituents has catapulted GESO into the spotlight in an unprecedented way.

An “Open Letter to GESO Leadership” expresses profound concerns about its organizing practices, particularly as these relate to women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and people of color. This renewed criticism of GESO has also come in the wake of heated debates on race and inclusivity on the Yale campus.

Days after the publication of the Open Letter in DOWN, GESO’s Coordinating Committee issued a response promising to reform its practices. GESO has agreed to reinstate its Equal Rights and Access Standing Committee; host an open forum regarding its organizing tactics; establish a relationship with Race Forward and other external organizations; and release a statement specifying its progress by March 11.

“All of us have made mistakes as we learn how to organize—we are not professional labor organizers, but academics who believe that a union is an essential step on the path to a more just and equitable university,” the letter reads. “A union is only worth having if it truly represents the consensus of its members.”

But for many signatories of the Open Letter, consensus still seems far out of reach. Many believe its organizing procedures were not only “mistakes,” as GESO claims, but clear breaches of privacy and dignity, executed in the name of a more “representative” union. For many, GESO will have to do more than merely re-brand itself in order to regain the trust of dissatisfied graduate students.

At the time this article was written, the Open Letter carried 148 signatures from current and former Yale graduate students. Attempts were made to contact all of the graduate signatories of the Open Letter. Forty-two graduate students responded to a request for an interview and 24 were interviewed over the course of two weeks.

Those interviewed are not representative of the graduate student body as a whole, but do offer an important insight into the conditions that inspired so many graduate students of color, women, and LGBTQ+ students to sign the Open Letter.

Across the interviews, graduate students recount systemic harassment, intimidation, and lack of empathy on the part of GESO organizers. However, the interviews also revealed a wide range of opinion on issues such as unionization and confidence in GESO’s planned reforms.

The majority of the signatories contacted only consented to give interviews for this article under the condition of anonymity. Some feared retribution from GESO as an organization, while others did not want to implicate their friends. Pseudonyms are demarcated with an asterisk (*).

These critics of GESO’s organizing tactics speak out in this exclusive report, which also includes an analysis of the results of a qualitative survey of these Open Letter signatories.

The Initial Meeting

While GESO claims to represent as much as two-thirds of the student body of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), Open Letter signatories reported joining the organization before they fully understood its aims and internal politics.

During the first few weeks of the academic year, GESO members typically convene an initial meeting for the first-year cohort in each department. Before the initial meeting, a member of one’s own first-year cohort is tapped to be the primary organizer for the new crop of students, while a senior GESO member is assigned to be the primary organizer for the department as a whole.

Quentin*, a PhD candidate in Music History (GSAS ’18), said each department’s organizing committee was “tapped” and “groomed” by GESO leadership leadership rather than elected by the students. In small departments, especially in the humanities, Quentin said, there is overwhelming social pressure to joining GESO.

Quentin signed a membership card it good faith, but several other interviewees recounted being strong-armed into signing membership cards. One interviewee said their repeated requests for written documentation as to the mission of the organization and its reasons for promoting unionization were denied.

Maggie Traylor, a doctoral student in History (GSAS ’20), described the first meeting in her department as extremely “tense,” and said she refused to sign a membership card right away. GESO organizers repeatedly emphasized that GESO already held an overwhelming majority within the History Department, and told her that most of her own cohort had already joined—this in a department with over 20 students per cohort. GESO also claimed to have a significant amount of faculty and administrative support within the department.

Traylor said she felt pressured to join GESO because she believed her refusal to join would have serious implications for her friendships and even her professional connections within the History Department.

A recent graduate in the sciences who identifies as genderqueer recalled being aggressively petitioned to organize their department in 2014. While they did not claim to be targeted by GESO, they said they might have been “misgendered” as one of the few “women” in their field, and later felt tokenized by the organization.

“Through conversations with someone close to the author of the open letter and hearing about some of the stories of other LGBTQ people, I realized that a token was most likely what GESO saw me as,” they said. “I wasn’t a person with an opinion and a past and a story.”

They never agreed to serve on the Organizing Committee, but endured two panic attacks during various encounters over several months with GESO organizers. They said these encounters consistently brought back memories of an emotionally abusive relationship, and eventually pushed them to seek therapy by the fall of that year.

A PhD student in the humanities said organizers’ recruitment tactics were persistent and violating of personal privacy, not unlike “sexual harassment.”

As a person of color, he questioned GESO’s claim to be an organization made up primarily of minorities and people of color, finding it “irritating” that the overwhelming majority of organizers who had approached him had been “elite, rich, white men,” with prestigious degrees from top-tier American and British universities. He said any doubts he expressed about the organization were labeled as conservative, despite his progressive political beliefs.

Traylor said that there are likely many more students who are critical of GESO who have been afraid to come forward. While she said she respected many GESO members, and did not want to disparage them, she was more suspicious of those “at the very top of the food chain.”

For those like Traylor who have lost confidence in the group, there is no formal membership rescindment mechanism in place.

“I believe in a union that wants a real consensus among students, not a mathematical one,” said Luca Peretti, a fifth-year doctoral student in the Italian Department. “They can say a hundred times that two-thirds of the graduate students are GESO members, therefore we have the majority. But we all know how a lot of them became members. What we do not know is how much the two-thirds believe in the union.”

Increasing the Pressure

After the initial meeting, signatories often experienced increasing pressure to take part in campus-specific campaigns, including canvassing for local political representatives, distributing petitions, and assuming increased levels of responsibility within GESO.

“My organizer would ask me to do things,” said a PhD candidate. “I would say no, and she would lean heavily on our friendship to get me to change my mind.”

Several signatories felt that GESO representatives deliberately cornered graduate students when they were alone and even emotionally vulnerable, exploiting the fact that graduate school itself is inherently isolating and stressful. One signatory said the tactics resembled “stalking.”

Under unrelenting pressure from the organization, Quentin joined the Coordinating Committee (CC) for a brief time, despite his consistent refusal and worsening health issues. While serving on the CC, Quentin and other CC members were consistently pressured to bring in “good numbers” while out canvassing.

“The numbers were everything (and some were clearly cooked: I know that we cooked numbers so we wouldn’t be yelled at by our organizers),” he said. “The ends justified any and all means.”

Furthermore, as he and many other former CC members would confirm, the CC had little influence with regard to GESO’s policies. Its role was to “rubber-stamp decisions made by the Steering Committee,” Quentin said.

Profoundly disillusioned by the inner workings of GESO, Quentin and the other organizers from the Music Department decided to quit the Coordinating Committee. Yet GESO members only pursued them more aggressively, repeatedly confronting Quentin and the Music Department organizers at their homes, unannounced.

Quentin received a cancer diagnosis soon after, and before he even had the opportunity to go home and call his family and partner, he ran into his organizer.

He did not want to reveal the diagnosis to his organizer, and told him only that it was serious and he needed to get home as soon as possible. His organizer was not at all sympathetic.

“At this most devastating of moments in my personal life, he cornered me and accused me of abandoning GESO when they needed me most.” Quentin said, “He said that I didn’t know what was best for myself. He said he was disappointed in me.”

Who’s in charge?

“Look at the demographics of Steering [Committee] versus CC [Coordinating Committee] and watch much of the diversity go away.”

—Former Coordinating Committee member

Many signatories cited GESO’s overall lack of transparency as a principal reason for adding their names to the Open Letter.

GESO’s response to the Open Letter was signed by the Coordinating Committee, composed exclusively of current graduate students, which GESO claims is its upper-level “elected leadership.”

But several signatories noted that the Coordinating Committee in fact occupies only the third-highest level of authority within GESO’s hierarchy, and its election process is far from democratic. Current CC members appoint new members, who are then approved by the CC, some signatories said.

Cheryl*, a former organizer and member of the Coordinating Committee, claimed GESO’s main leaders are employed by UNITE HERE: Anita Seth, the Staff Director of Local 34, Yale’s clerical and technical workers’ union, and Jeffrey Boyd, the regional organizing director for UNITE HERE. In email correspondence, Cheryl wrote that she eventually left GESO because she “realized the extent to which Anita and Jeffrey (and by association UNITE HERE) run the entire union and the lengths they will go to get the numbers they think necessary,”

“Why are the decision-makers of GESO not even graduate students?” she asked.

Under Boyd and Seth is the Steering Committee (SC), made up of approximately ten members, although it’s unclear who sits on the Committee, Cheryl said.

The Steering Committee meets every day in a closed-door meeting, but “from the CC meetings, it seems Jeffrey and Anita tell them what to do, and then they pass it down to the CC,” she said.

Three other signatories who had been involved in GESO shared the same suspicion about the top-down structure of the organization. Paula*, a PhD student who had been a member of her department’s Organizing Committee (OC) in Fall 2012, said student input about what GESO should be was repeatedly shot down farther up the chain of command. She said their nearly identical responses were “canned,” and she began to suspect that the Steering Committee had in fact told other organizers what to say in advance.

Since that time, GESO has indeed implemented some of the ideas that Paula suggested, including creating a Facebook page and hosting several teach-ins, but the organization never credited her for those ideas.

“We never got around to doing any of that exciting work we’d thought we’d do because we were so busy trying to get more people to join. It was like a classic pyramid scheme,” Paula said.

In its response to the Open Letter, the GESO Coordinating Committee describes itself as “a leadership group made up overwhelmingly of women, people of color and LGBTQ people.” But several former CC members reported that the Steering Committee was overwhelmingly white, heterosexual, and male, at least around late 2014.

“Look at the demographics of steering versus CC,” said Cheryl, “and watch much of the diversity go away.”

Citywide Stakes

GESO’s alignment with the New Haven unions Local 34 and Local 35, representing thousands of Yale employees, places it in the middle of a larger, citywide discussion on the expanding power of a less-than-transparent labor coalition. GESO’s massive rally last year of over a thousand, including the governor, the mayor, and various state representatives, reveals the high political stakes of GESO’s fight for recognition on a larger stage.

During the summer following his first year, summer 2013, Quentin said he was pressured to canvass for Toni Harp’s mayoral campaign, even though he did not personally support her, citing “allegations of corruption and negligent property management that have been leveled against her family for decades.”

His organizers confronted him with a choice: walk in support of Harp, or face being viewed as a bad example—as he put it, a “bad member of the union.”

“Nevertheless, I was eager to be a good member of the union,” he said. “Like so many others have done, I fell prey to their liberal-conscience guilt-tripping.”

Quentin claimed GESO provided its representatives with very little information about the Harp campaign before sending them out into various neighborhoods to solicit support.

“I came to recognize a hard truth,” Quentin said. “We weren’t being sent out to convince voters with real details about policies candidates actually represented.”

GESO has also become an important player in Yale’s relationship to Locals 34 and 35.

In an email sent out by Marcy Kaufman, the graduate registrar of the History department, she wrote that Locals 34 and 35 were facing “serious issues of attrition,” and implied that a new union, GESO, might help to fill the void. She also warned that the burden on faculty as well as graduate teachers would increase tremendously with the University’s plans to add two new residential colleges, and urged graduate students to demonstrate their solidarity with all the employees of the University by contributing to GESO’s Fall 2014 photo campaign.

“In order to shift the conversations with the University,” she wrote, “we need to show our support for GESO and solidarity with each other. I’m asking you to take a stand.” Kaufman did not respond to a request for an interview.

Representing Graduate Students

The question of unionization has acquired a new urgency in the face of an imminent ruling by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) on whether graduate students at private, nonprofit universities should be classified as employees. A ruling in favor of this classification could force a vote among Yale graduate students as to whether or not they would agree to be represented by GESO.

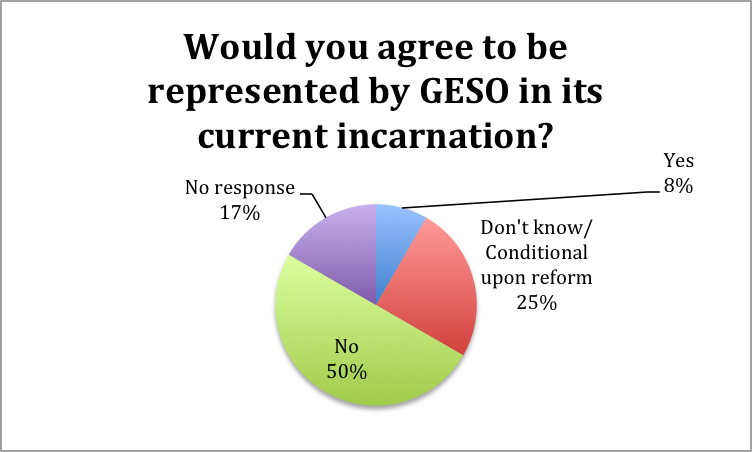

Half of the signatories interviewed said they would not consent to be represented by GESO in its current incarnation, but a quarter expressed some ambivalence, saying they were not sure, or would only agree to be represented by GESO if it demonstrated significant reform.

Only 8% of interviewees said they would agree to be represented by GESO if the issue were to be put to a vote tomorrow, yet those in this group also articulated significant misgivings about GESO. A first-year PhD student in the humanities said she would only vote “yes” because she was unaware of any alternatives, but did believe in unionization.

Peretti said that while reforms are in order, representation by GESO would be better than not having a union at all.

“We desperately need a union that can represent us and speak for us, and we need a contract that recognizes our labor,” Peretti said. “A bad union can be improved and changed, a non-existent union cannot.”

When pressed, the overwhelming majority of respondents could not envision any current organization other than GESO that would take up the unionization effort, though it is apparent that many wanted an alternative.

“GESO takes up all of the air space,” Traylor said.

Another second-year doctoral student observed that GESO had perhaps created the perception of a complete monopoly on the cause of graduate students’ rights.

“Opting out of GESO does not preclude an individual from believing in, advocating for, and advancing the causes that GESO itself advances,” she said. “But GESO wishes to eradicate this alternative, to monopolize its proletarian agendas.”

A small fraction of interviewees, however, saw other existing avenues for political representation within the University. A doctoral student in the humanities said he supported the idea of “a body of elected representatives [that would] advocate for our interests,” but did not want to be represented by GESO.

Rather, he claimed the Graduate Student Assembly (GSA) already fulfilled this role, explaining that the organization “has a history of working productively with Yale’s administration, and […] has achieved significant advances, the latest notable one being a marked improvement in graduate funding packages.”

Other sources mentioned that alternative political work apart from unionization could also be done within existing organizations, for example the Graduate and Professional Student Senate (GPSS), and organizations such as the Graduate Association of French Students (GAFS), which allows students to serve as faculty-student liaisons within the French Department.

Some interviewees, on the other hand, supported more grassroots movements. Quentin, for example, said he would favor a coalition led by the signatories of the Open Letter.

“After dealing with GESO, I just stopped thinking about [a union]. I knew I didn’t want GESO to be it.” Traylor said. I decided to put my head down and focus on classwork because that’s what I came here to do.”

Hope for GESO

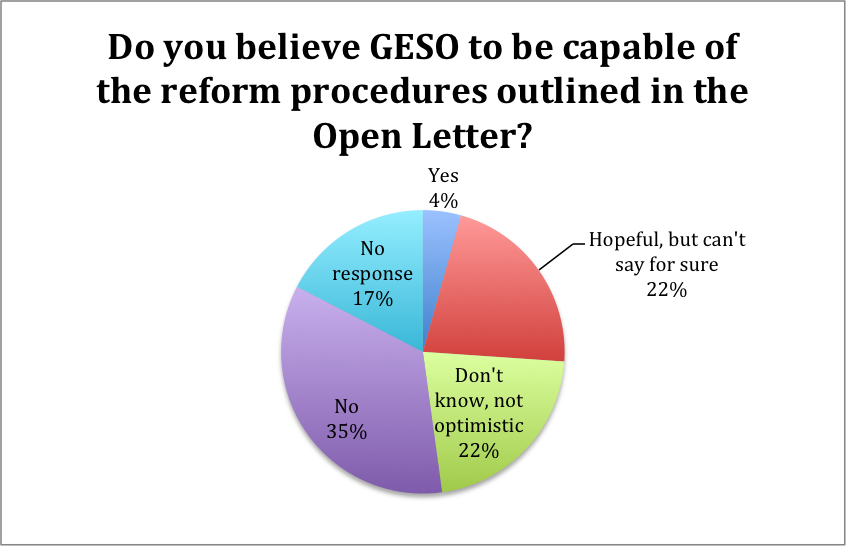

More than a third of interviewees had absolutely no confidence that GESO would carry out the reforms proposed in the Open Letter. While insisting on the general honesty of many GESO representatives, Paula said she expected more from GESO’s response to the Open Letter, namely an appropriate admission of guilt, as well as greater recognition of the demands of the Open Letter.

“I had hoped that they would acknowledge that [the] specific organizing tactics the letter describes […] are violent and inappropriate,” Paula said. “I’d hoped that the CC would promise to ban those tactics, and to re-train organizers accordingly. I had also hoped that GESO would hire an external advisor, as the letter demanded.”

Paula went on to express her frustration that GESO also did not consent to reevaluate its relationship with UNITE HERE. Rather, she suggested that GESO relied on the demographic structure of the Coordinating Committee as a bargaining chip, and as insurance against further criticism.

“Instead they just told us that there were lots of women, LGBT people, and people of color on the CC,” said Paula. “We know that. The problem isn’t about individuals; the problem is structural.”

Despite fierce criticism of GESO as it stands today, more than a fifth of survey participants were optimistic that the reforms proposed by GESO will be carried out.

“I really hope that most of the people who are in this are in it for the right reasons,” said Traylor. She was pleased to see that GESO had issued a response to the Open Letter and did acknowledge these complaints to some degree through this gesture.

“That seems to be progress to me in some way, shape, or form,” she said.

*Names have been changed to protect the anonymity of contributors.

Holly Chung (GSAS 2018) is a PhD student in Music History, a signatory of the Open Letter to GESO Leadership, and a former GESO member.